Kate Called the Shots in 'Call Me Kate'

'Call Me Kate' is for the fans. It's an intimate account of an iconic film star.

Incluvie Foundation Gala - Learn More

Nothing but snow for miles. All that meets the eye is a white, pure as a celestial’s love for their soulmate. In that freezing land, cold as the heart of a woman trapped in a loveless marriage, passion is a rare sight. And it’s where Abigail (Katherine Waterston), lives with her husband Dyer (Casey Affleck), trying her best to cope with the loss of her daughter while doing the job of a homemaker. Their conversations make it plenty clear that the attachment has become commoditized over the ages, the marriage gradually shrinking into a mere functional entity, despite the love not having faded away. In that bleak existence, a new neighbour, especially a pretty woman like Tallie (Vanessa Kirby) provides a source of much-coveted companionship. And it’s the bond forged between the two navigating the pitfalls of married life that lights a fire even the fierce life-threatening blizzard cannot blow out. It burns with the passion of a wildfire, but their extenuating circumstances prevent its proliferation.

The visual grammar of The World to Come is the most powerful tool at director Mona Fastvold’s disposal to convey the frenzied nature of the relationship between Abigail and Tallie. For example, the first time they meet, Abigail is dressed in black, while Tallie wears a white dress. This possibly acknowledges that Abigail is in a state of mourning for her lost child, and is also the more repressed of the two. Tallie, at the moment, is a fresh presence in her life. It might also be foreshadowing for the reveal that she’s isolated in her marriage, as her husband Finney (Christopher Abbott) is harshly unappreciative of her. However, at the moment, she also represents a gift from the world for Abigail. Everywhere she looks outside, it’s white, and then Tallie walks in from outside, dressed in white, a stark contrast from the inside of her house, which is dimly lit in the daytime, and definitely distinct from the brightness that Tallie seems to exude by just being herself. Moreover, the way the camera lingers on Tallie’s hands, as she fidgets with her cuff, or on her face as Abigail narrates to us, how she perceived Tallie, makes abundantly clear, the nature of the affection Abigail wanted to engage.

The play on colours continues when Abigail and Dyer visit Tallie and Finney. Now Abigail’s in a red gown, while Tallie’s dressed in black. Abigail seems to have found a newborn interest with love, now that she was occupied all the time with thoughts of her newfound companion, and this liveliness is reflected in the red. Tallie, on the other hand, is still perceived as a source of intrigue and definitely authoritative in Abigail’s perception because she longs for Tallie to take command as she’s still bereft of words. Even before that, the first time they make physical contact, a subtle movement from Tallie as her finger creeps over and curls around Abigail’s, the frame is shot with the fireplace in the background. It’s a much less subtle metaphor for sure, but I believe it’s the visual representation of the richness of the emotional journey set in motion by that one slight touch. The first kiss actually has Abigail take the lead, and interestingly she’s in black, the image of authority, while Tallie’s in white, hesitant in her innocence. On the other hand, their riskiest moment, in Abigail’s house, has Tallie in black, as she takes control as the temptress, leading the pure Abigail into uncharted territories of thrill.

On the matter of representation, the film’s title, as Vanessa Kirby herself mentioned in an interview with The Guardian, is a nod to the fact that this is a world inherited by women from less fortunate ones, and hopefully being passed on to more fortunate ones. The deplorable plight of women who were mere possessions of their husbands, in the 19

century, in which the film is set, happens to be the central focus of the rift between Tallie and Finney. Finney repeats verses from the Bible to support his claim that Tallie shouldn’t behave like her own person, and her importance derives from the necessity of her existence, as decided by him. The misogyny is confronted head-on, in their marriage, and it’s not watered down for the comfort of the audience, except for a modesty in presentation which reflects on the time it’s set in. You’ll not see fights like in Big Little Lies between Nicole Kidman’s and Alexander Skarsgard’s characters. Like everything Abigail, the situation in her marriage is addressed much more subtly, most memorably in the form of an exasperated observation she makes to herself. She says ‘Daughters are married off so young that everywhere you look, a slender and unwilling girl is being forced to stem a sea of tribulations before she is even full-grown in height.’ She laments about her plight as who doesn’t even appear in her husband’s records beyond the rare purchase of an expensive dress, despite the innumerable chores she completes, for which she’s taken for granted.

While film and TV still have a long way to go when it comes to LGBT representation, there are so many more opportunities for LGBT people to see themselves onscreen than there were even a few years ago. Best of all, some of the best LGBT films and shows are available online for free or on popular streaming services that you might already be subscribed to. Here are some of my top picks for films and TV shows with positive LGBT representation, sorted by where you can find them. (Note: This list is accurate as of June 2021, but streaming libraries change frequently.)

Tubi offers a library of over 20,000 movies and shows for the unbeatable price of zero dollars, as long as you're willing to put up with a few ads.

Must-Watch LGBT Movies Online Recommendations

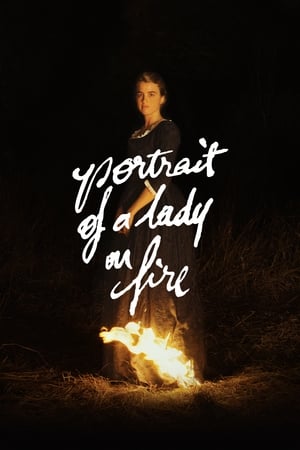

Portrait of a Lady on Fire, from director Céline Sciamma, tells the story of Marianne (Noémie Merlant), a painter living in eighteenth century France who is tasked with painting a portrait of Héloïse (Adèle Haenel), a woman who is to be married off soon. Initially painting her in secret, Marianne develops a close bond with Héloïse and slowly begins to fall for her. What follows is an intimate, poetic, and moving love story that sweeps the audience up in a beautiful, breathtaking feat.

Portrait of a Lady on Fire is stunning, down to the way the movie looks, the sound design, and the nuanced performances of Merlant and Haenel. Every frame of the film is a painting, gentle and composed like the most beautiful pieces of art. It’s impossible to look away from, and it’s completely mesmerizing.

The cinematography done by Claire Mathon is stunning, with every shot feeling like an integral part of the movie. The cinematography is a character in and of itself, and portrays the lushness of the story just as much as the words themselves do. Art is a key part of the film’s story, and this is reflected in the way it looks and the gentle, natural sound, free of any musical score until the achingly beautiful finale. Portrait of a Lady on Fire succeeds at placing the audience in the film, making them feel as though they are a part of that place and time, though in reality it is so distant.

Francis Lee’s much-anticipated period romance, Ammonite, stars Kate Winslet and Saoirse Ronan as two women who fall in love against the backdrop of the English coast. Ammonite is both more and less than I expected, with Winslet and Ronan delivering stellar performances in a story that doesn’t quite live up to its potential.

Lee opens the film with an extended shot of a nameless woman scrubbing a museum floor. A group of men barks at her to move as they carry a fossil across the room. The scene effectively, if rather unsubtly, establishes the theme of devalued female labor.

We then meet Mary Anning (Winslet), a paleontologist eking out a bleak existence with her distant mother (played sublimely by Gemma Jones). Mary’s passion is excavating and studying the fossils she finds in the cliffs along the English Channel, but she makes ends meet by selling trinkets to tourists. Mary’s bitterness and loneliness stem from a series of traumas that largely remain implied. It’s been far too long since Winslet had a role with this much depth, and her powerful yet restrained performance alone makes Ammonite worth a watch.

The World to Come (2021) is an astonishingly beautiful love story. Mona Fastvold’s nineteenth century lesbian romance is emotionally charged, restrained, and poetic without feeling forced. Helped along by the incredible performances of its cast and its gorgeous visuals, the film tells a story of isolation and connection, bleakness and joy.

The World to Come is focused on two couples working hard just to survive on the American East Coast frontier in the 1850s. Abigail (Katherine Waterston) and husband Dyer (Casey Affleck) have recently lost a daughter to diphtheria, and they’re struggling with grief that leaves no room for closeness between them. Tallie (Vanessa Kirby) and her unrelenting husband Finney (Christopher Abbott) have begun renting a farm close by. When Abigail and Tallie meet they form an instant connection, a stark contrast from their previous isolation.

The film is narrated by diary entries from Abigail. The poetic narration is beautifully worded and performed and gives a deep view into Abigail, who is not an outwardly emotionally effusive person. Katherine Waterston’s voiceover narration of the diary entries is just one part of her stunning performance. Her Abigail is quietly desperate — intense yet controlled, at different moments achingly lonely, joyful, anguished. Vanessa Kirby, too, gives a remarkable and passionate performance.

From the moment that the two first lock eyes, the chemistry between Abigail and Tallie is the most striking element of the film. Their strong, clear connection adds to the tension that underscores the entire film. The two light up when together and you can feel their ache for each other when separated, a separation that is made necessary at times due to the unyielding land and at times due to their husbands. The tension at moments in the film, driven by the relationship between Abigail and Tallie and their relationships with their respective husbands, is so palpable it feels as if you could cut through it with a knife.

The World to Come is visually stunning, using gorgeous natural imagery. The world of the film is often bleak and sparse, yet it’s captured very beautifully. Its overall atmosphere alternates between coldness and warmth with an underlying darkness, which adds to the fiery nature of the film and its central relationship. The film’s visuals also work with the soundtrack to create an incredibly atmospheric film.

On an isolated island in Brittany at the end of the eighteenth century, a female painter is obliged to paint a wedding portrait of a young woman.

Céline Sciamma

Director

Céline Sciamma

Director

Noémie Merlant

Marianne

Adèle Haenel

Héloïse

Luàna Bajrami

Sophie

Valeria Golino

La Comtesse

Christel Baras

La faiseuse d'ange

Armande Boulanger

L'élève atelier

Guy Delamarche

L'homme salon

Clément Bouyssou

Le batelier

'Call Me Kate' is for the fans. It's an intimate account of an iconic film star.

The major flaw of the series is that it’s hosted on Netflix and barely makes malicious comments about it despite being focused on the lives of people directly affected by the Capitalist mentality of the OTT corporation.

Season 1 of Love, Victor ended on a major cliffhanger: Victor came out to his parents. He said the words “I’m gay” for the first time. Now what? Season 2 answers the question: “What happens after coming out?”