Revisiting the Holy Trinity of Aroace Disney Princesses for Pride Month

Although not canonically aromantic or asexual. the stories and personalities of these Disney princesses resonate with members of the aroace community.

Incluvie Foundation Gala - Learn More

Nothing but snow for miles. All that meets the eye is a white, pure as a celestial’s love for their soulmate. In that freezing land, cold as the heart of a woman trapped in a loveless marriage, passion is a rare sight. And it’s where Abigail (Katherine Waterston), lives with her husband Dyer (Casey Affleck), trying her best to cope with the loss of her daughter while doing the job of a homemaker. Their conversations make it plenty clear that the attachment has become commoditized over the ages, the marriage gradually shrinking into a mere functional entity, despite the love not having faded away. In that bleak existence, a new neighbour, especially a pretty woman like Tallie (Vanessa Kirby) provides a source of much-coveted companionship. And it’s the bond forged between the two navigating the pitfalls of married life that lights a fire even the fierce life-threatening blizzard cannot blow out. It burns with the passion of a wildfire, but their extenuating circumstances prevent its proliferation.

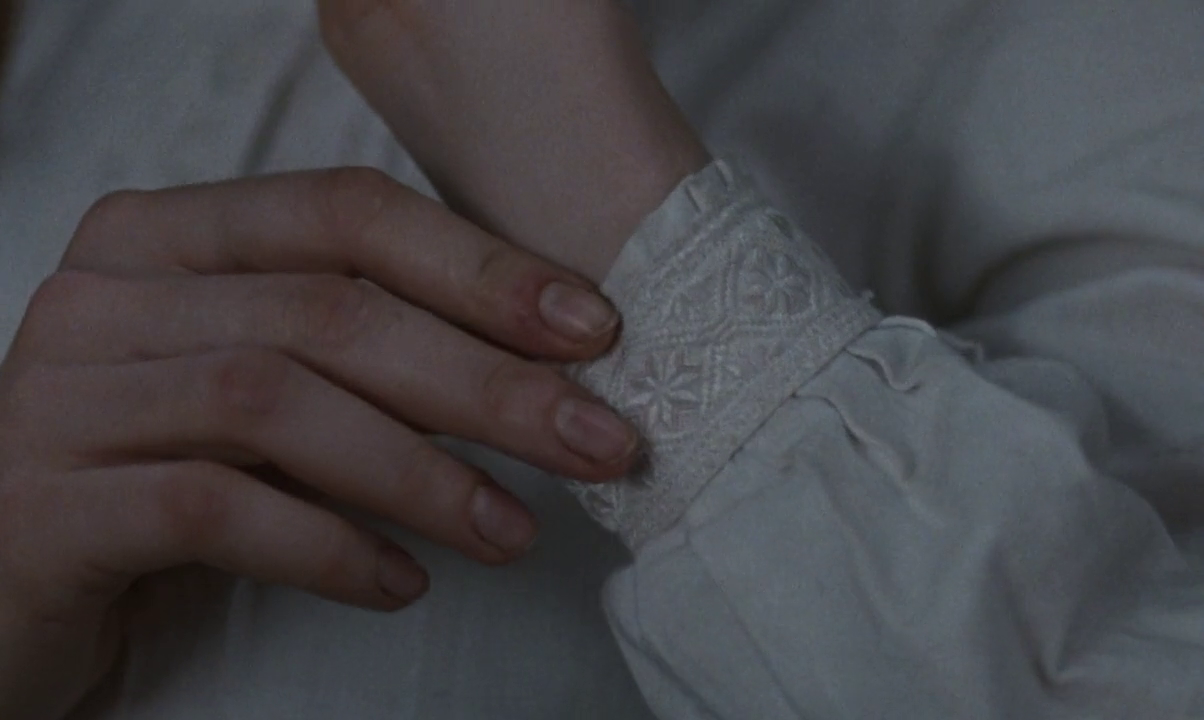

The visual grammar of The World to Come is the most powerful tool at director Mona Fastvold’s disposal to convey the frenzied nature of the relationship between Abigail and Tallie. For example, the first time they meet, Abigail is dressed in black, while Tallie wears a white dress. This possibly acknowledges that Abigail is in a state of mourning for her lost child, and is also the more repressed of the two. Tallie, at the moment, is a fresh presence in her life. It might also be foreshadowing for the reveal that she’s isolated in her marriage, as her husband Finney (Christopher Abbott) is harshly unappreciative of her. However, at the moment, she also represents a gift from the world for Abigail. Everywhere she looks outside, it’s white, and then Tallie walks in from outside, dressed in white, a stark contrast from the inside of her house, which is dimly lit in the daytime, and definitely distinct from the brightness that Tallie seems to exude by just being herself. Moreover, the way the camera lingers on Tallie’s hands, as she fidgets with her cuff, or on her face as Abigail narrates to us, how she perceived Tallie, makes abundantly clear, the nature of the affection Abigail wanted to engage.

The play on colours continues when Abigail and Dyer visit Tallie and Finney. Now Abigail’s in a red gown, while Tallie’s dressed in black. Abigail seems to have found a newborn interest with love, now that she was occupied all the time with thoughts of her newfound companion, and this liveliness is reflected in the red. Tallie, on the other hand, is still perceived as a source of intrigue and definitely authoritative in Abigail’s perception because she longs for Tallie to take command as she’s still bereft of words. Even before that, the first time they make physical contact, a subtle movement from Tallie as her finger creeps over and curls around Abigail’s, the frame is shot with the fireplace in the background. It’s a much less subtle metaphor for sure, but I believe it’s the visual representation of the richness of the emotional journey set in motion by that one slight touch. The first kiss actually has Abigail take the lead, and interestingly she’s in black, the image of authority, while Tallie’s in white, hesitant in her innocence. On the other hand, their riskiest moment, in Abigail’s house, has Tallie in black, as she takes control as the temptress, leading the pure Abigail into uncharted territories of thrill.

On the matter of representation, the film’s title, as Vanessa Kirby herself mentioned in an interview with The Guardian, is a nod to the fact that this is a world inherited by women from less fortunate ones, and hopefully being passed on to more fortunate ones. The deplorable plight of women who were mere possessions of their husbands, in the 19th century, in which the film is set, happens to be the central focus of the rift between Tallie and Finney. Finney repeats verses from the Bible to support his claim that Tallie shouldn’t behave like her own person, and her importance derives from the necessity of her existence, as decided by him. The misogyny is confronted head-on, in their marriage, and it’s not watered down for the comfort of the audience, except for a modesty in presentation which reflects on the time it’s set in. You’ll not see fights like in Big Little Lies between Nicole Kidman’s and Alexander Skarsgard’s characters. Like everything Abigail, the situation in her marriage is addressed much more subtly, most memorably in the form of an exasperated observation she makes to herself. She says ‘Daughters are married off so young that everywhere you look, a slender and unwilling girl is being forced to stem a sea of tribulations before she is even full-grown in height.’ She laments about her plight as who doesn’t even appear in her husband’s records beyond the rare purchase of an expensive dress, despite the innumerable chores she completes, for which she’s taken for granted.

The need to hide their story from the rest of the world due to a lack of understanding is never addressed. I particularly liked this approach to writing where the elephant in the room is never addressed. In fact, the expression of love itself comes in the form of seemingly unrelated poetry, and almost everything about them as a couple is never talked about. Their love needs no language beyond the language of the body. The curling lips, the sparkling eyes, the fiery red colour of Tallie’s hair, the caresses, the kisses and so and so forth. Say all there is to say as if an attempt to articulate it will falsify it, or make the risks too concrete to think beyond. And yet, there’s no lack of words in the narrative. Abigail’s superior skills as a writer shine through, as she speaks to the audience to express her emotions: ‘Her image provoked a sensation in me like the violence that sends a floating branch far out over a waterfall’s precipice before it plummets’. The poetry is not just visual, and the articulation of the ineffable, makes the cinematic experience more engrossing, captivating the mind with the words.

‘We hold our friendship between us and study it, as if it were the incomplete map of our escape.’ The imprisonment they already felt about their existence is somehow accentuated by the unique nature of the companionship because it’s introduced something more that they’re being kept away from. And it’s in the fleeting moments of bliss when they’re in each other’s arms, feeling the pleasure that had become alien to them, that they’re able to escape their predicaments. The way Abigail sits at her table, hands askew like Jesus on the Cross, unable to stop saying ‘Astonishment and joy’ after their first kiss, addresses this redeeming quality of the bond they share. It’s a bold visual, as she mimics the prophet of the religion which seemingly forbids same-sex relationships and preaches complete submission of a woman to the man who owns her residence. In fact, there seems to be no misappropriation, and the scenes of intimacy, are just visuals of undying passion, threatening to burn down any obstacle in its path, but actually living silently in the hearts of the participants, whispering the feeling that Tallie so eloquently articulates as ‘All our burdens will be lightened.’

Both lead actresses deserve loads of acclaim. Vanessa’s beautifully embodied the risqué Tallie, as she challenges Abigail at every moment, provocatively giving her signals, always a pleasure to behold in her element as a sight of pure beauty, gracefully dancing her way through the days. And Katherine Waterston’s reserved performance as Abigail is possibly even more enjoyable. She brings a new layer of truth to her words ‘when it came to speaking and attempting to engage another’s affections, circumstances doomed me to striving and anxiety.’ As a writer, she only speaks on paper and prefers to think to herself otherwise, while Tallie struggles to make poetry out of her emotions, but boldly proclaims ‘It’s been my experience that it’s not always those who show the least who actually feel the least.’ Their chemistry is the right amount of hushed, and the slow burn is palpable in the lack of physical intimacy on screen. The subtle behavioral hints are the perfect way to develop the narrative. And they’re the ideal companion to the dreamy voice with which Katherine narrates Abigail’s thoughts.

‘There is something going on between us that I cannot unravel.’ At the heart of The World to Come, lies this silent proclamation of love. As a period drama about lesbian women, unfairly treated by their husbands, it’s a truly touching ode to the redeeming power of love. It really can touch you one time and last for a lifetime, as Celine Dion memorably sang once. In one unexpected moment of clarity, Tallie claims ‘Maybe they had a certain high hopefulness that we don’t have’, when Abigail speaks of the courage of the ancestral women she admired. And it’s the ability of the film to make me feel this way about the characters on the screen, that pushes me to claim this is a fresh story, despite this slowly becoming an overdone niche of a genre over the last few years, with films like Ammonite and Portrait of a Lady on Fire. It could ignite in you an appreciation for life like only love stories for the ages can. ‘How pleasant and uncommon it is to make someone’s day’, Tallie once said, and so, I believe did the film.

Related lists created by the same author

Although not canonically aromantic or asexual. the stories and personalities of these Disney princesses resonate with members of the aroace community.

Related diversity category

Love, Simon (2018) based on the book “Simon vs The Homo Sapiens Agenda” (by Becky Albertalli) is a teen LGBTQ+ rom-com with themes of longing to find others with similar struggles, and ultimately is a story of acceptance of identity from those around you, and most importantly, from yourself.