'iCarly' Reboot (2021 TV Series)

A reboot series based on the popular original Nick teen sitcom of the same name.

Incluvie Foundation Gala - Learn More

Frances McDormand is unquestionably one of the greatest actresses working today. Her recent Best Actress Oscar win for Nomadland (2020) has all but confirmed this notion, as she managed to top some of the stiffest competition the category has seen in years. Her performance in Chloe Zhao’s neo-western is the latest to deftly demonstrate her commanding ability to defy the preconceived expectations of women, especially women her age. There are strong hints of feminism to many of the characters she brings to life, and never in a way that feels overbearing. Moreover, despite the fact that many of her characters are inherently fictional, there is an even greater degree of truthful candor to them, largely due to how delicately she interprets them. Her characters don’t just break stereotypes so much as they also do so in a way that feels entirely natural and unquestionable. McDormand’s three Academy Award-winning performances are the most evident proof of how she is able to convince us she’s just a person going about her day, all but making us forget about her celebrity status. However, in a long and storied career, her most productive effort in this regard is that in her first winning turn in Fargo (1996).

Since the rise of the independent film movement of the 1980s and ‘90s, few combinations have been as effective as McDormand and her husband, Joel Coen. As filmmakers, Coen and his brother, Ethan, are practically a genre unto themselves. A Coen brothers movie is one with its own set of rules, its own understanding of human nature. A Coen brothers movie will not hesitate to subvert audience expectations and find the levity in even the most perilous of situations — a grisly murder could have just occurred and you’d still be hard pressed not to let out a slight chuckle. A Coen brothers movie peels back layers to reveal the morose underbelly of an idyllic landscape, a kind of disturbing realization that can only be found when you stop and take a look around. A Coen brothers movie can be damn near anything it wants to be, cause a whole lot can happen in the middle of nowhere. And no other entry in their distinguished oeuvre embodies such a sentiment better than the black comedic crime thrills of Fargo. It stands to reason as to why Coen’s perennial leading woman feels like such a natural choice as the headliner of the movie.

Playing upon the conceit that what is to unfold is based on true events, Fargo follows car salesman, Jerry Lundegaard — whose greedy, but dim-witted nature is perfectly embodied by William H. Macy — as he hires two equally greedy and dim-witted thugs to kidnap his own wife in order to extort a hefty ransom from his father-in-law and settle his many debts. And, of course, as is the case with many a Coen-penned story, pretty much everything that could possibly go wrong does exactly that, which leads to the arrival of pregnant police officer Marge Gunderson as she relentlessly works to track down the inept criminals disturbing the peace in the quiet, snow-covered Minnesotan landscape.

To understand a film like Fargo is to understand everything that it’s not and everything it should never be labeled as. It is by no means typical in terms of its narrative structure, character development, or general outlook on the human experience. At first glance, it might be only too easy to accuse the film of being underwhelming, especially in comparison to the rave reviews and many accolades it accumulated upon its release. But that’s kind of the idea. It’s a movie that’s worth multiple watches, and leaves your eyes glued to the screen each and every time, because its story exposes the various anachronisms of suburban life that couldn’t possibly be revealed in a single glance. At a time when big-budget studios were in the throes of male-centered action movies, senseless comedies, and dark thrillers, a little independent film with a strong female presence proved that you can combine the best elements of all these genres and touch upon something more profoundly human than anything that came before.

For all of its outlandish genre-mashing, Fargo more often than not feels like a legitimately real story with characters you might meet on the street or in a dingy bar. Such is the strength of the Coen brothers’ gift of gab and their keen understanding of what audiences presume to know about the movies and their relationship to society. Audiences often assume that a character’s pregnancy has significant weight on the plot and would make her weaker in their eyes. Audiences often assume that criminals are always one step ahead and know what makes their victims tick. Audiences often assume that well-to-do suburban husbands with a loving wife and son would not descend into a world of shady embezzlement and arranged kidnappings. And audiences would assume that a movie called Fargo would have more than just one scene set in North Dakota. But that’s not how this movie works, and, more importantly, that’s not how life works. Life is measured in the small problems that are made all the more outrageous by the folly of incompetent men whose attempts at rectification simply create more problems. Fargo affirms this notion by purposefully misdirecting the viewer and reminding us all that life, in essence, is but one giant mess.

You can hear this movie title

Steven Spielberg’s summer classic has been around for nearly half a century, making it impossible to write about without spoilers. As a cultural touchstone, Jaws has launched a thousand parodies, tributes, and memorable quotes. It’s also been a PR nightmare for sharks.

A private detective takes on a case that involves him with three eccentric criminals, a beautiful liar, and their quest for a priceless statuette.

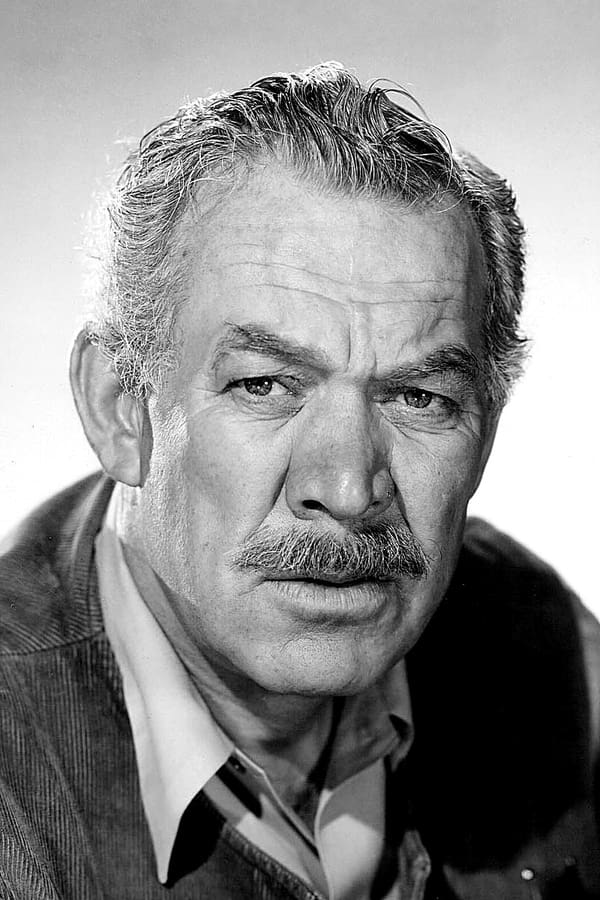

John Huston

Director

John Huston

Director

Humphrey Bogart

Samuel Spade

Mary Astor

Brigid O'Shaughnessy

Gladys George

Iva Archer

Peter Lorre

Joel Cairo

Barton MacLane

Lt. of Detectives Dundy

Lee Patrick

Effie Perine

Sydney Greenstreet

Kasper Gutman

Ward Bond

Det. Tom Polhaus

Jerome Cowan

Miles Archer

Elisha Cook Jr.

Wilmer Cook

James Burke

Luke

A reboot series based on the popular original Nick teen sitcom of the same name.

'Kajillionaire' is a touching and eccentric story about family, crime, and the search for belonging.

“Jumanji - a game for those who seek to find, a way to leave their world behind...” A nostalgic classic that remains unnerving, "Jumanji" draws audiences into a chilling adventure.