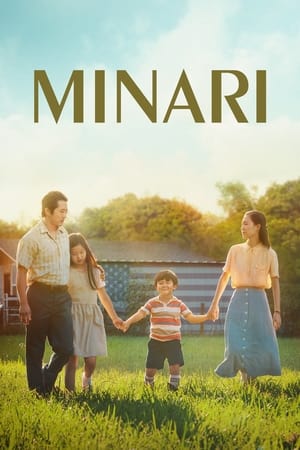

South Korean media, especially music and movies, has been on the rise in international popularity lately. From Train to Busan, to Parasite, to Minari, to Squid Game, we are in an absolute golden age of Korean entertainment. However, the more Korean films you digest, the more likely one question will pop up: what's North Korea doing? There's not much the general public knows about North Korea except for what's put on the news. However, since it's a closed society, people can't help but be curious as to what lies inside. As a naturally curious person, I wanted answers, and to me, one of the best ways to get a quick helping of culture is by watching their movies. As you can imagine, there aren't many (at least that we know of) North Korean films and many of them were created by dictator Kim Jong-il who had a passion for film. Though, that is when I discovered the famed Pulgasari (1985), the North Korean Godzilla film with a wild story.

Kim Jong-il loved cinema so much that, he established an underground operation to get bootleg copies of international films that were banned in North Korea, much to the dismay of his father Kim Il-sung. He supposedly gathered a library of over 15,000 movies and especially liked action movies such as James Bond. Eventually, he decided he wanted to make his own films and was employed as the director of the Motion Picture and Arts Division in the Propaganda and Agitation Department. Soon, Kim discovered that he hated how inferior his casts and crew were in comparison to the West’s. So, he began to obsess over Shin Sang-ok, a proclaimed director in South Korea.

Kim Jong-il was convinced that Shin was the only person who could save the North Korean movie industry, so he created an elaborate plan to kidnap him. He managed to lure Shin's recently divorced wife, actress Choi Eun-hee, with a forged offer to direct movies in Hong Kong. She was then abducted in Hong Kong and brought to North Korea. All according to plan, Shin Sang-ok began to search for his ex-wife and traveled to Hong Kong, where he was chloroformed and brought to North Korea.

Shin attempted to escape the country multiple times, resulting in him being imprisoned in a North Korean prison camp. After four years of imprisonment, Kim decided that Shin was ready to direct films, released Shin and Choi, and brought them to a meeting. The dictator asked them to make communist propaganda and to claim that they came to North Korea due to repression in the South. Shin agreed to cooperate and was showered with the greatest luxury the country could gather. To create the special effects for the film, Kim also tricked a Japanese special effects team (the one who created the original Godzilla movies) to come to North Korea when they were believed to be working in China.