Sweet Girl's Mind-Boggling Twist Makes the Movie... Feminist

For the most part, 'Sweet Girl' recycles tired hyper masculine revenge tropes, but a surprise twist in the end turns it into a female-centric revenge film.

Incluvie Foundation Gala - Learn More

Most interracialist films are superficial mirrors reflecting our simplistic views and wishes for race and ethnic relationships. You People is as superficial and shallow as its forbearers.

People often pat themselves on the back for watching "progressive" Guess Who's Coming to Dinner style movies. They beam with pride despite the little to nigh nonexistent internal reflection about the colorist tropes and implications in said movies. The same people who dismiss race as "just" a social construct, as if their paycheck, relationships, morality, and national identity (to name a few things) are not also social constructs with real-world implications, will champion the "bravery" of movies that explore interracial love. How they can classify these relationships as interracial while purporting to not buy into race because it's "just" a social construct is anyone's guess. It is just as confusing as ever-color-struck Kenya Barris' motivation for creating this mediocre redux. Barris is a controversial colorist, having espoused that mixed people will be "in" in the near future, implicating that he promotes the lighter skin, racially ambiguous aesthetic for practical purposes. It's really just his latest excuse for colorism. Once again, a Black creator with problematic views on colorism, misogynoir, and questionable representation is elevated over more thoughtful ones.

You People follows the formula you expect from another slog into glossed-over sexual racism, desirability politics, misogynoir, and colorism disguised as a progressive commentary. This film is as shallow and superficial in its commentary as most American conversations regarding race relations. Ezra (Jonah Hill), a white male that you are allowed to assume is white based on his phenotype (remember this, it'll be important later), falls for Amira (Lauren London). Amira is essentially coded as Black in the film, despite a throwaway line that tries to explain away why she has ambiguous features and lighter skin by suggesting her mother (Nia Long) has a white grandfather. The film already distrusts its own logic. If Amira's phenotype is perfectly common for the daughter of two dark skin, unambiguously Black parents, why do we need a discount genetics lesson? Barris and Hill likely knew that many Black viewers would scratch their hair at the fridge logic and continued colorist tradition of casting Biracial and Multiracial actresses to play Black women on film. Something tells me they were not educating people on genetic admixture in African Americans. One can not help but wonder why Amira was not created as a biracial character. Could Ezra not have fallen in love with a biracial woman? Then there would be no need for this plot hole masking as a plot contrivance, and there would be no dark skin erasure in this casting.

But alas, the racist one-drop rule strikes again.

The movie makes as much sense as this setup. Predictable hijinks ensue as we watch the couple and their respective families follow a flattened "love conquers all/we are all one race the human race" contrived plot. There is nothing novel about this movie or interracial relationships (they've been happening long before Eurocentrism came along) despite it using "modern" in the tagline. There are a lot of white-centered interracial romance films that superficially gloss over the problematic aspects of the marriage market and its reliance on Eurocentric beauty standards. You People is simply another one.

There’s a lot that can be said of You People, a recent comedy film released through Netflix starring Jonah Hill, Lauren London, Eddie Murphy and Julia Louis-Dreyfus. It covers the somewhat cinematically underdeveloped and occasionally controversial subject of interracial and interfaith marriage and the ensuing clashes between older and younger generations on the matter. The film bravely, in my opinion, addresses a generalized ignorance both Black and white people possess in their dealings with each other. You People puts words to things that we’ve all thought about from time to time but never had the courage or willingness to admit to. And leave it to the comedy genre, and producer, writer, and star Jonah Hill, to cover the topic with enough humor and candidness to not alienate its audience. Instead, the film attempts to invite the audience into a much needed discussion.

Praise and critical accolades, however, are not the things that seem to be following You People since its release. Despite debuting at number one on Netflix, the film’s success has been somewhat overshadowed by a recent article that claimed the two main characters, Ezra and Amira, never actually kissed in the film’s closing scene. Co-star Bill Schultz recently commented on his podcast that on set the two actors paused before their lips locked and that one of the film’s most intimate moments was actually created by CGI.

What’s the point of this strange yet fascinating bit of news? For me, the article implies there’s a certain fraudulence to the movie. How can you portray a love story between two people and not have them actually kiss? If a romantic comedy is a cookbook, the kiss is an essential ingredient. The authenticity and message of the film are called into question.

This might be an overblown reaction, however. This "news" arguably does not mean anything and may not even be true. And if it were true then so what? Maybe the production saved money by not hiring an intimacy coordinator. Or perhaps the writers decided that scenes of an intimate nature were unnecessary, that the story was less about expressions of love and more about interracial couples and their dealings with societal and familial expectations.

The aforementioned familial expectations take the form of two sets of parents. Arnold and Shelley, played by David Duchovny and Julia Louis-Dreyfus. The other parents are Akbar and Fatima, played by Eddie Murphy and Nia Long. Jonah Hill plays Ezra, a young, Jewish, up-and-coming podcaster who meets Amira (Lauren London), a fashion designer, after inadvertently getting into the back seat of her car, mistaking her for an Uber driver. The movie then jumps ahead a few months to find them living together as a couple. Deciding that they want to take their relationship to the next level, they realize they must first introduce themselves to each other's respective parents.

Since George Floyd was murdered by police on May 25, 2020, we have seen protests erupt in all 50 states within the United States and 50 countries across the world on every continent except for Antarctica. The United States has sanctioned unchecked police brutality for far, far too long; a symptom of the systemic racism of a country that was built by slaves upon stolen land. Since May 25, the stories of murdered innocent Black people have been shared, as well as countless videos of the police brutalizing protestors at anti-police brutality protests.

There have been Black Lives Matter protests in the past. There have been riots, and officers have used tear gas and rubber bullets. What we are seeing on the news and in our neighborhoods is not new, but it has never been quite like this. Putting COVID concerns aside, people are taking to the streets to protest and raise awareness about the corruption of the police force in the United States, the inequality of the criminal justice system, and the systemic racism that is at this country’s heart.

For white people, this is a time to listen. We need to listen to Black people and hear their stories. We need to self-reflect and assess how our privilege has shielded us from much of the ugliness and terror that Black people experience daily. White people need to be vocal about their disdain for the actions of the police and the system of oppression within the United States. At the same time, we need to genuinely listen to other people and hear exactly how this country operates and functions differently for Black, Indigenous, People of Color than it does for white people.

I have always believed that movies can change the world; they hold the power to examine topics that many people are uncomfortable discussing. Movies can get the ball moving so that we have a starting point from which the conversation can begin.

This is a list of seven films that explore police brutality and systemic racism made by Black filmmakers. These are important movies to watch and to take in, as — through the power of cinema — they showcase what it feels like to be a Black person living in a country that is internally designed to be against you.

Since George Floyd was murdered by police on May 25, 2020, we have seen protests erupt in all 50 states within the United States and 50 countries across the world on every continent except for Antarctica. The United States has sanctioned unchecked police brutality for far, far too long; a symptom of the systemic racism of a country that was built by slaves upon stolen land. Since May 25, the stories of murdered innocent Black people have been shared, as well as countless videos of the police brutalizing protestors at anti-police brutality protests.

There have been Black Lives Matter protests in the past. There have been riots, and officers have used tear gas and rubber bullets. What we are seeing on the news and in our neighborhoods is not new, but it has never been quite like this. Putting COVID concerns aside, people are taking to the streets to protest and raise awareness about the corruption of the police force in the United States, the inequality of the criminal justice system, and the systemic racism that is at this country’s heart.

For white people, this is a time to listen. We need to listen to Black people and hear their stories. We need to self-reflect and assess how our privilege has shielded us from much of the ugliness and terror that Black people experience daily. White people need to be vocal about their disdain for the actions of the police and the system of oppression within the United States. At the same time, we need to genuinely listen to other people and hear exactly how this country operates and functions differently for Black, Indigenous, People of Color than it does for white people.

I have always believed that movies can change the world; they hold the power to examine topics that many people are uncomfortable discussing. Movies can get the ball moving so that we have a starting point from which the conversation can begin.

Get Out follows Chris and Rose (an interracial couple). As their relationship continues to flourish, the couple embarks on a small journey. Rose, a Caucasian women, takes Chris, an African American male, to her parents house. At first, the family seems friendly, but as time progresses, it’s clear that something is off. Simply put, Jordan Peele’s film is an intelligent and unflinching piece of work, firmly focused on an African American story in fiction. At first, it’s a charming form of interaction. Like Stanley Kramer’s “Guess Who’s Coming To Dinner” (1967), the familial atmosphere is filled with humor and playfulness. However, as time moves on, the film enters sinister territory, echoing the slow burn style of Roman Polanski’s “Rosemary’s Baby” (1968) and Bryan Forbes’ “The Stepford Wives” (1975).

It’s no wonder Peele won an academy Award for Best Original Screenplay. His script is layered with perspective and subtlety. Through a terrific vision, Peele creates the gift that keeps on giving. The clues and symbolic representations are aplenty, and as each viewing passes, you are destined to find something new. That’s a mark of great cinema.

Essentially, Peele’s script touches on aspects like the taboo nature of societal marginalization, racial cliches, and interracial relationships. The film, as a whole, presents an unfiltered vision of humanity, telling us that some citizens are full of corruption and misguidance. Like the horrific monsters and ghouls we see on the big screen, real life human beings are capable of performing evil tasks. Like a responsible film should, “Get Out” holds a mirror up to society, forcing its inhabitants to look at the ugliness that lies within.

Another strong suit of this script is the efficiency of characterization. Peele’s characters have purpose. As Chris, Daniel Kaluuya gives us a sympathetic character, designed to be a quintessential “every man.” As Rose, Allison Williams provides us with an adorable character, consisting of sincerity and mystery. The rest of the family enhances the tense proceedings. Whether it be Bradley Whitfield’s sappy, outlandish charm, Chatherine Keener’s deadpan seriousness or Caleb Landry Jones’ slimy portrayal, the family is a versatile unit of evil. Through these unique characterizations, this socially charged film is given life.

A couple's attitudes are challenged when their daughter brings home a fiancé who is black.

Stanley Kramer

Director

Stanley Kramer

Director

Spencer Tracy

Matt Drayton

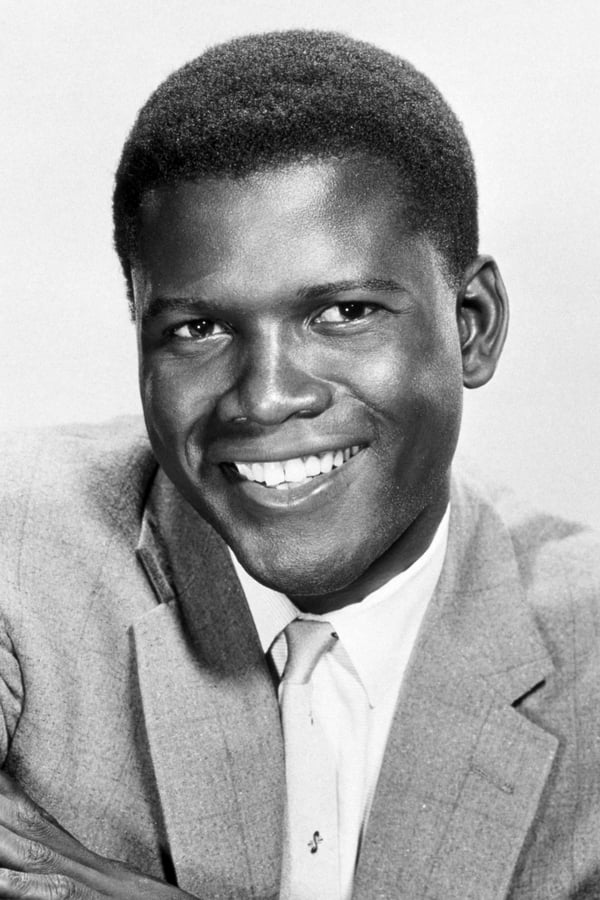

Sidney Poitier

John Prentice

Katharine Hepburn

Christina Drayton

Katharine Houghton

Joanna "Joey" Drayton

Cecil Kellaway

Monsignor Ryan

Beah Richards

Mrs. Prentice

Roy Glenn

Mr. Prentice

Isabel Sanford

Tillie

Virginia Christine

Hilary St. George

Alexandra Hay

Carhop

Barbara Randolph

Dorothy

For the most part, 'Sweet Girl' recycles tired hyper masculine revenge tropes, but a surprise twist in the end turns it into a female-centric revenge film.

Severance is about breaking down facades and confronting old models that were once frameworks of our lives. The somewhat subtle message to me is it’s never too late to fall in love, no matter your insecurities.

In 'Maestro,' we're left with an impression but not with an understanding of the main character.