The 60th New York Film Festival closed its main slate of screenings with The Inspection. The festival’s artistic director, Dennis Lim, introduced the film as a beacon for the future of cinema and a high note on which to end, signaling, for a festival presenting the work of directors both seasoned and burgeoning, one of the voices that will color cinematic storytelling for years to come. The film is significant not only for its excellent composition, its amplification of a historically marginalized narrative, and its empathy (the single most powerful tool in any filmmaker’s kit), but also because it is the transposition of its director’s, Elegance Bratton’s, lived experience.

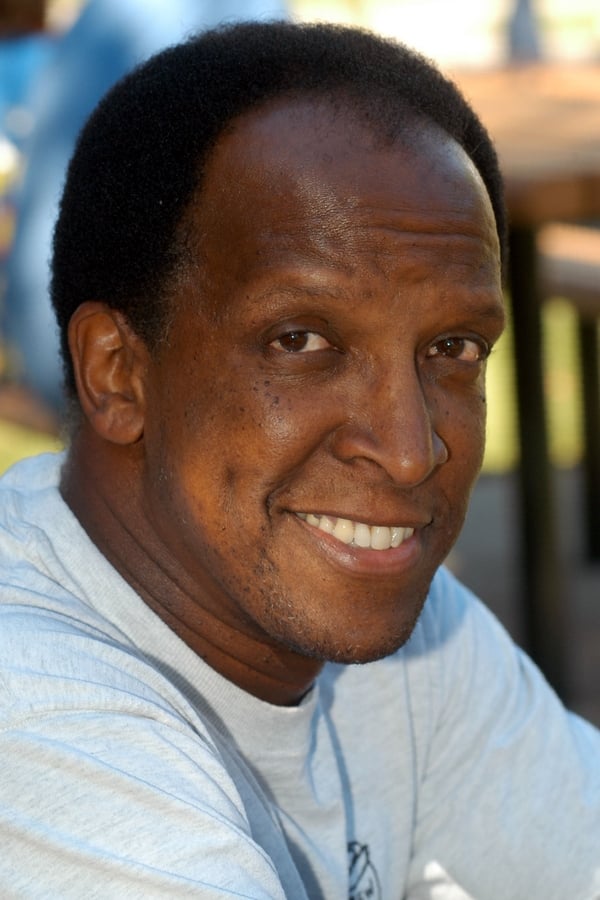

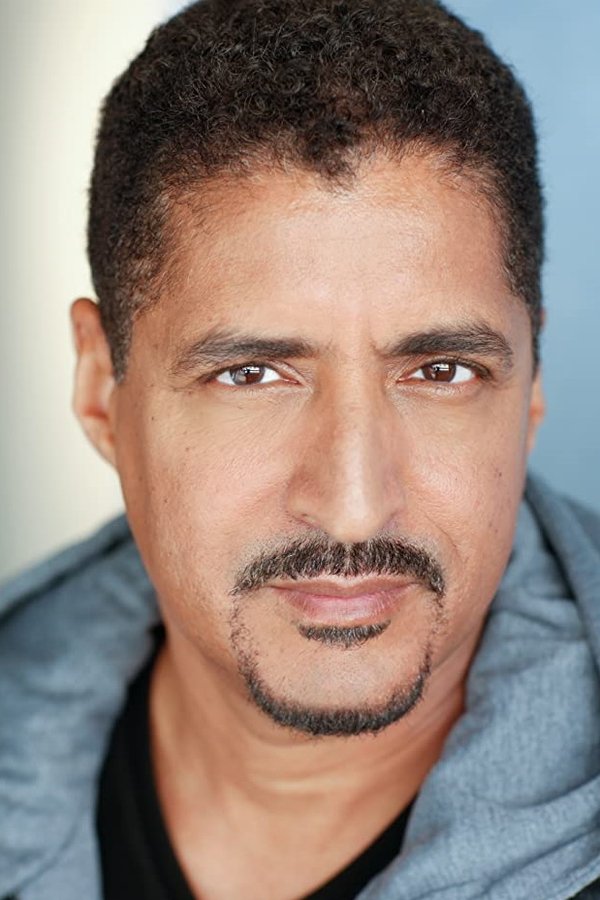

Bratton’s first feature film outside of the documentary genre, The Inspection is a retelling of his experience as a gay man in Marines bootcamp. It is an auspicious debut, filled with empathy, tenderness, humor, and humanity, all the more effectively deployed for its juxtaposition against the harsh, hypermasculine backdrop. The protagonist, French (played by an incandescent Jeremy Pope), having been homeless for 10 years, joins the Marines to win the love and respect of his homophobic mother (Gabrielle Union, who also produced the film), whose only show of support is to give her son the birth certificate he needs to enlist. (If you return a failure, she says, “consider this document void.”) What begins as a quest to rekindle a semblance of a mother-son relationship transforms into a fight for survival and preservation of identity when French is outed as gay in the presence of his recruit platoon.

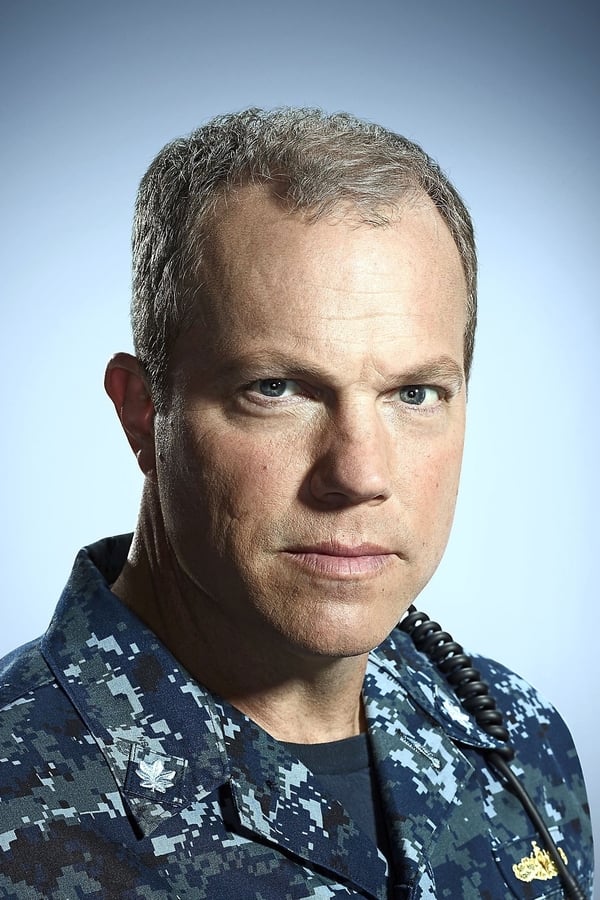

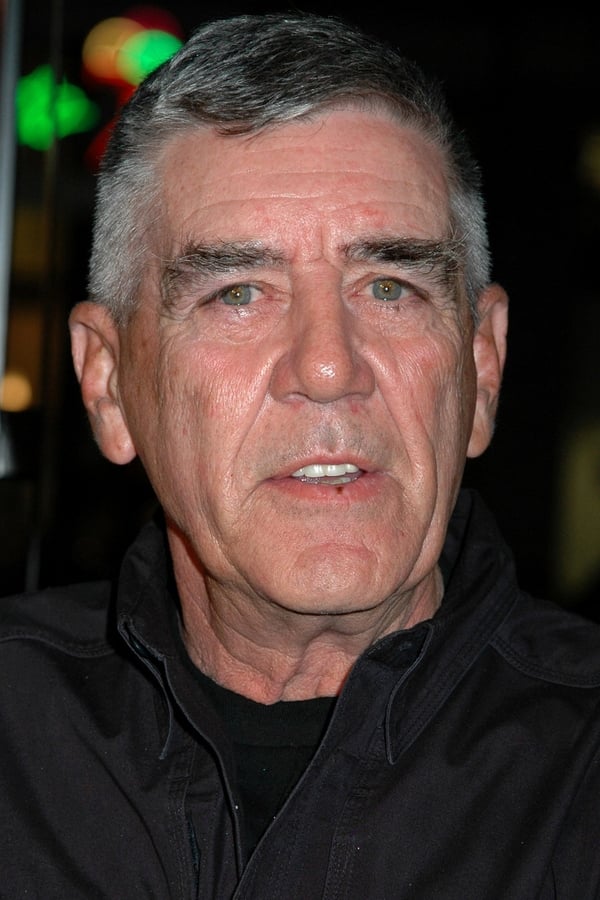

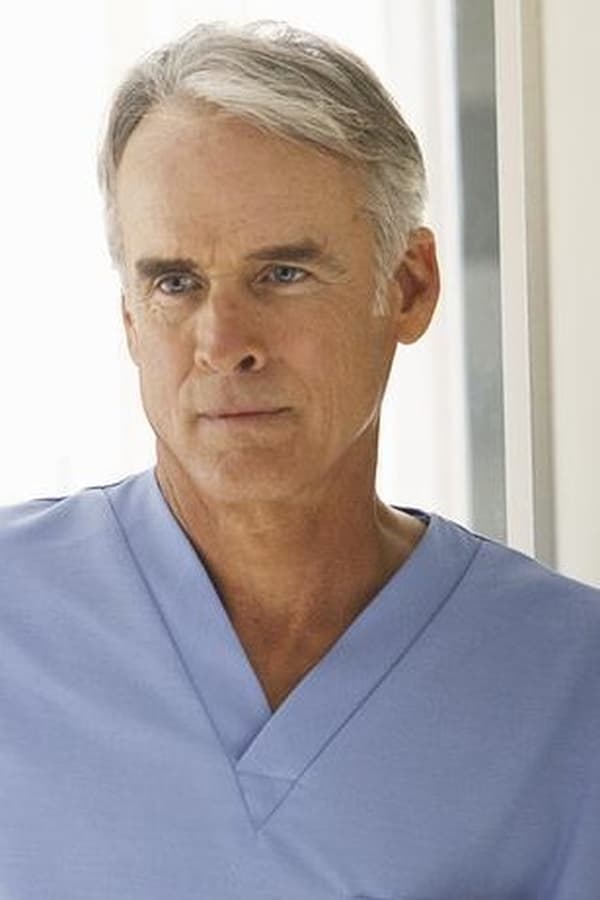

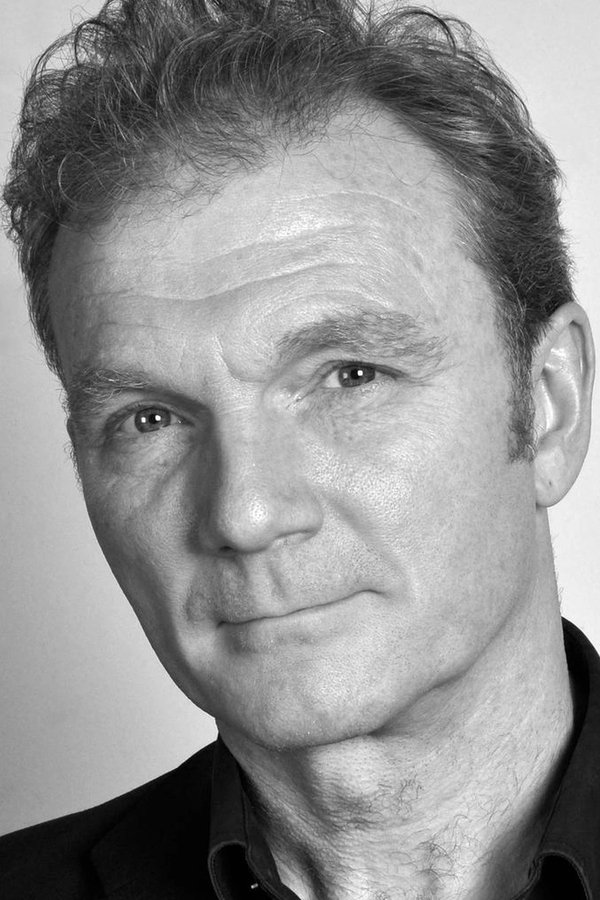

French immediately becomes the recipient of homophobic hazing and abuse from his fellow recruits—some of whom deny their friendship with him to remain on good terms with their gung-ho squad leader—as well as their austere training instructor, Leland Laws (Bokeem Woodbine), whose indiscriminate attempts to break his recruits and turn them into killing machines are taken to the extreme with French. After Laws nearly drowns French during a rescue exercise, French finds a comforting allied voice in Laws’s right-hand man, Rosales (Raúl Castillo), who embodies the supportive camp counselor role to Laws’s hateful, authoritarian methods.

Throughout the film, Bratton does not limit the thematic relevance strictly to French’s emotional turmoil. The empathy that French receives from Rosales, life-saving at times, is the same tenderness with which the director handles various subplots and narrative arcs. French extends his own care and resolve to his fellow recruits, acknowledging the shared struggles of bootcamp, the tests of mental fortitude, and the religious conformity imposed by the military. Moments of humor shine through and highlight the human element of the narrative (a room full of horny recruits masturbating underneath bedsheets, French repurposing warpaint into queenly drag makeup for the final training exercise, the Crucible). The small moments of humanity give depth to the harsh setting of French’s turmoil. The film is not so callous as to make an enemy out of every character other than the protagonist.

Even French’s mother’s judgement—which is easy to reduce to hateful toxicity, given her overt homophobia—is characterized through the director’s gentle lens as a shit kicker’s flaw; she gave birth to her son at 16 and is no stranger to hardship. Union’s roiling “holier-than-thou” soliloquies flesh out a woman much more substantial than a one-note antagonist. French is not alone in his struggles. Bratton, having lived the experience himself, is blessed with this knowledge, and the film’s ability to empathize with each of its characters benefits from his singular insight.