Incluvie Foundation Gala - Learn More

Call Me by Your Name (2018)

Incluvie Related Articles

Visi-Bi-lity: It's Improving!

September 5, 2022Before I start, I feel the need to clarify that by bisexual, I’m talking about sexuality directed towards members of more than one gender identities. I’ll admit that the clarification will seem pointless since the films I’m about to mention barely involve characters who aren’t either male or female. However, that is due to the lack of gender-queer representation in media and not how I personally perceive bisexuality.

Now, bi-erasure, for those who might not know, simply identifies the often common phenomenon of bisexuality not being acknowledged. This can be in cinema, music, art, novels, or even in real life. This has happened to every community that falls under the umbrella term 'queer', you might be thinking. However, bisexuality has a more prominent history of being subjected to this. Bisexual coming-out scenes are extremely scarce, and most bisexual stories acknowledge only homosexual tendencies or otherwise just portray bisexuality as a phase or an experimental experience. It sometimes manifests from the urge to steer narratives away from heteronormativity. In an attempt to portray heteronormativity negatively, homosexual experiences are highlighted to the point where bisexuality doesn’t get acknowledged. So is it really queer-positive if it comes at the cost of bi-erasure?

A very common form of bi-erasure is when a character who’s only had heterosexual experiences, starts experiencing homosexual tendencies and is then shown to realize that they were homosexual all along and pretended to be heterosexual. This is bi-erasure because quite often, the character might just be bisexual, and by saying they finally realized they’re gay, the narrative is essentially erasing the possibility of the character being bi. If only a few stories were of this kind, it wouldn’t be an issue, but this is extremely rampant (Brokeback Mountain, Call Me By Your Name, and Teorema to name a few, are all considered to be gay films).

One of the most classic examples of bi-erasure from Hollywood in the 21

Century is Jennifer’s Body. Starring Megan Fox as the titular Jennifer, the film was marketed as an overly sexual horror film that specifically caters to the male gaze of heterosexual adolescents. However, its cinematography is abundant in the female gaze, which usually includes focusing on hands, lips, and eyes, sensuously but emotionally perceiving the characters on screen. The male gaze, on the other hand, tends to focus on the body itself, with a certain lust in its framing of female characters specifically. Plus, Jennifer Check actually says the words “I go both ways” in reference to her sexual preference. Still, being perceived as a heterosexual narrative is blatant bi-erasure. However, I have good news for you. The film is being re-evaluated and reclaimed as an important work in queer horror.

Wolfwalkers Deserves More Acclaim Than Luca For Pride Awareness Through A Metaphor

November 25, 2021Cartoon Saloon is really coming into its own with its distinct style of art, and personal narratives to tell compelling stories about the world. The 2017 film The Breadwinner is one of the most haunting English animation films I have ever seen. And the studio lived up to that, with another powerful story in Wolfwalkers. It’s about a misfit girl Robyn who ventures outside into the woods and becomes friends with a mysterious girl Mebh who morphs into a wolf. She has a personal vendetta against people because they’re encroaching into the woods. However, she’s timid when friendly, and once even vulnerably admits her mother is missing. At night, Robyn discovers she’s morphed into a wolf.

It’s a vampire-esque origin story, with Robyn’s morphing triggered by Mebh’s bite mark, which she made as a wolf. To avoid spoilers, it’s not possible to go into details about how extensively the film develops the metaphor for being queer. Robyn can live up to her free-spirited soul, and runs through the forests with her new friend Mebh after she transforms into a wolf at night. The bite mark is practically a euphemism for the eye-opening experience many have, which makes them realize why they were not fitting into this aggressively heteronormative world. Often it takes another person to show us our truth, and then leave us to explore for ourselves. That’s exactly what the first half’s about.

Luca, Disney’s pride month release, takes a slightly different approach. There, the story is told from the perspective of those who are aware of themselves. They consciously hide from the rest of the world. Here, they’re sea creatures which the people think are monsters. They never go to the land. However, when a kid, Luca, does cross over, he realizes, he gets transformed into a person, and can perfectly fit into the world. Here also, there’s another daring kid, Alberto, who guides him, like in Wolfwalkers with Mebh for Robyn. They feel adventurous and decide to try life as people for some time. It’s essentially the same story, however, when taken literally, the symbolism is a bit problematic.

If the monstrosity is really a metaphor for queerness, I’m not sure it sends a good message to depict them blending into the regular world, and finding it adventurous and fun. It almost gives being heterosexual, a ‘forbidden fruit’ touch. In fact, the conclusion of Luca makes it clear why they chose such a bizarre depiction, but that makes it feel quite like propaganda made to categorically come across as an ally. Actually, Luca is too much of a Disney movie to make sincere commentary. Wolfwalkers doesn’t shy away from portraying the dysphoria that arises from trying to belong in a heteronormative society. Luca does that too, but the beginning is the other way round and that’s a puzzling choice.

Many have said Luca is an animated kids version of Call Me By Your Name. Visually, I agree. It’s got a similarly dreamy colour palette, and the town looks familiar for anyone who’s seen the Guadagnino film. However, Call Me By Your Name, is actually more similar to Wolfwalkers thematically. There, the unsuspecting protagonist was introduced to their latent sexuality by another person, and they secretly explore that. In Luca, they’re both aware and are bored with being themselves, so they secretively pretend to be straight to reap the benefits of being heterosexual. There’s truth in the fact that there is hetero privilege in the world, but Luca never crosses the line into questioning the perception of heterosexuality as ‘normal’.

Pictures and Videos

Movie Information

In 1980s Italy, a relationship begins between seventeen-year-old teenage Elio and the older adult man hired as his father's research assistant.

Cast

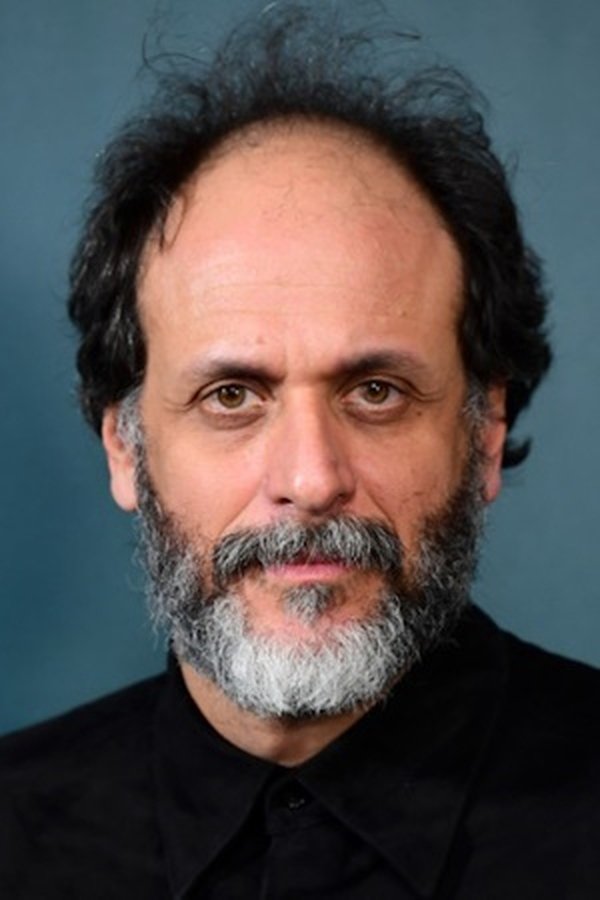

Luca Guadagnino

Director

Luca Guadagnino

Director

Armie Hammer

Oliver

Timothée Chalamet

Elio

Michael Stuhlbarg

Mr. Perlman

Amira Casar

Annella

Esther Garrel

Marzia

Victoire du Bois

Chiara

Vanda Capriolo

Mafalda

Antonio Rimoldi

Anchise

Elena Bucci

Bambi

Marco Sgrosso

Nico

André Aciman

Mounir