Bardo, False Chronicle of a Handful of Truths is the most recent shining example that disproves the old adage “numbers don’t lie.” I’m thinking, of course, of the oft-misleading and perennially dubious Rotten Tomatoes score that too often decides the viewing fate of commercially released films today. Alejandro G. Iñárritu’s latest film currently holds a 56% on the review aggregator, a failing grade in the American public school system. It’s a shamefully low number and a criminally inaccurate representation of its quality; the only boon the rating serves is to temper expectations and disarm a willing viewer as they enter a surrealist cinescape most reminiscent of

Federico Fellini’s 8 ½. The stylistic similarities are impossible to ignore, and the subjectivity of a revered filmmaker, the focal point in

8 ½ and

Bardo, is amplified to the n degree in Iñárritu’s film. It is through the keyhole of a single clever plot point—obscured behind the veil of memory but at all times right before our eyes—that Iñárritu serves us a portrait of a life lived in

Bardo, a Buddhist transitional state, where a single person dissolves into everything and nothing at once.

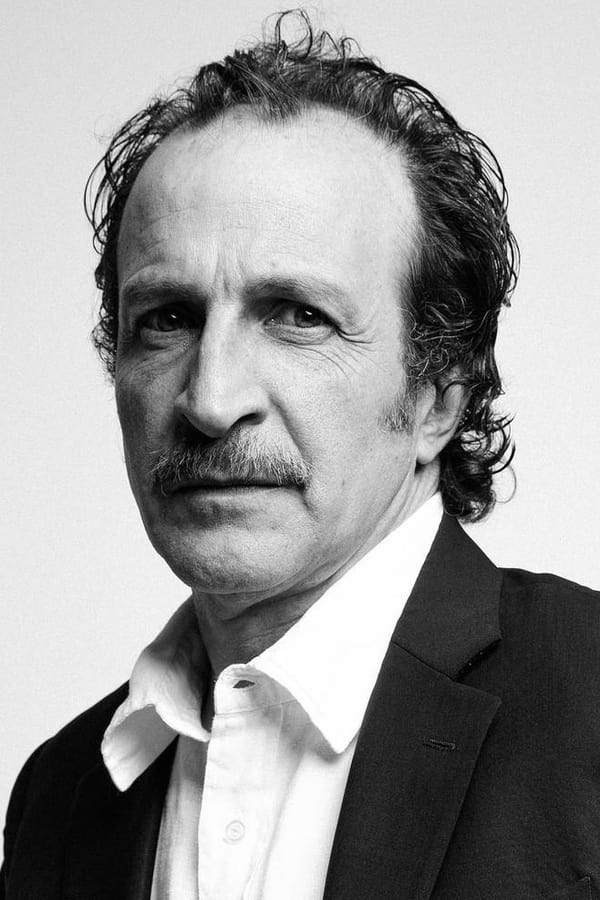

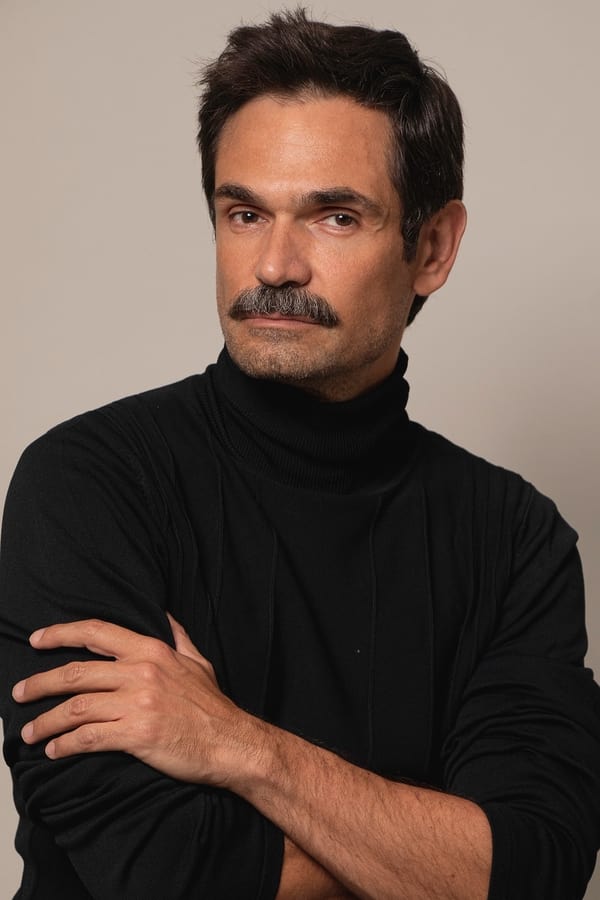

The film places the viewer into the mind (as literally as possible through the cinematic medium) of a fictional documentary filmmaker, Silverio Gacho (Daniel Giménez Cacho),

a stand-in for Iñárritu. Silverio harbors a love-hate relationship with his mother country, Mexico. His decision to raise his children north of the border colors his relationship with his family and the citizenship he claims. Widely revered for his work, Silverio prepares to accept a prestigious American award for journalism following the release of his film, entitled “False Chronicle of a Handful of Truths.” Scenes from his film are melded seamlessly into the larger narrative, alongside Silverios personal memories, and prove to be visceral reckonings with his own familial life and his relationship to his Mexican identity. The film is endlessly self-referential, nonchronological, and completely oneiric from minute one. Darius Khondi’s cinematography, full of long takes, point of view perspectives, strategically placed mirrors, and

large-format, wide-angle shots