The history of Hollywood is as ugly as it is beautiful. You can go back and look at decades of iconic films that have graced the silver screen, from Gone with the Wind (1939) to Citizen Kane (1941) to North by Northwest (1959). Most notably absent from Hollywood history, however, are Black-produced films. When movies did feature Black characters, they were always written by White writers and directed by White directors. The stories were never centered around Black people focusing on what it means to be Black.

Developed by Simon Frederick, They’ve Gotta Have Us (2018) is a limited series on Netflix that explores the rise of Black cinema in Hollywood. From The Birth of a Nation (1915) to Black Panther (2018), and everything in between, They’ve Gotta Have Us offers a comprehensive and compelling look at Black representation in film and the surge of Black-produced cinema.

I’ve mentioned before that some of my favorite classes I took in college were film history courses. I love contextualizing movies and seeing how every film influenced the next. However, I learned virtually nothing about the parallel history of Black cinema in Hollywood. They’ve Gotta Have Us proves to be incredibly enlightening, exploring so many facets of Hollywood history that were previously unknown to me.

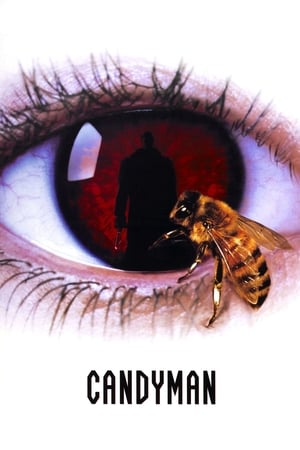

The series features interviews with prominent Black filmmakers such as Barry Jenkins (Moonlight, If Beale Street Could Talk), Laurence Fishburne (School Daze, The Matrix), David Oyelowow (Selma, A United Kingdom), Kasi Lemmons (The Silence of the Lambs, Candyman), John Boyega (Attack the Block, Star Wars: The Force Awakens), Gina Prince-Bythewood (The Secret Life of Bees, Beyond the Lights), Carmen Ejogo (Selma, It Comes at Night), and Robert Townsend (Hollywood Shuffle, The Five Heartbeats).

Going into the series, I would have assumed that Black voices had been suppressed in the industry for decades even if I didn’t necessarily know all of the details beforehand; I had no idea the extent to which this happened. The beginning of the series looks at the early years of Hollywood. The Birth of a Nation (1915) defined the motion picture and shaped everything about what movies are and how they are made. Director D.W. Griffith did not believe Black actors were capable of giving the performances he wanted, so he cast White actors in blackface to play horrific caricatures.