Diversity Programming At The Austin Film Festival

Coverage from the Austin Film Festival, highlighting some panels and films that emphasized the importance of diverse and inclusive storytelling.

Incluvie Foundation Gala - Learn More

The more and more I consume media, be it literature, theatre, television, etc., the more I’ve come to understand that art is a reactive medium. The narratives we see explored are a response to the world we inhabit and the conflicts we experience as a society. Because of this, even when a specific topic has been addressed previously, there are always nuances to be further excavated, always a new lens to peer through, to see aspects that have yet to be showcased onscreen. And with something as complex as racism and the stereotypical representation of “Blackness,” we are in need of as many interpretations as we can get to even begin to comprehend the full scope of this lived experience.

Enter Cord Jefferson’s sharp, hysterical, enlightening satire, American Fiction, which places an only-somewhat-exaggerated mirror in front of our 21st century society. Adapted from Percival Everett’s book, Erasure, and boasting a cast of seasoned actors, each of whom has their own history of portraying the nuances to the Black experience, the film tells you what it is going to be from the first frame; and not only does it not disappoint, it proves to be even more wise, even more cunning than you could begin to imagine possible.

In order to fully appreciate the conversation Jefferson is exploring in this film, one must understand that Black cinema has its roots in parody and satire.

Historically, the systemic racism within Hollywood made it essential for Black filmmakers, writers, and storytellers to create their own media, because the white directors’ lens could not capture the authenticity of that community’s existence. And a lot of those white filmmakers used their stories to reinforce racist and degrading imagery, so it was imperative for artists like Oscar Micheaux to step up and demand their own seat at the table; to create story worlds that resembled their own, with characters, themes, and music that spoke to their daily lives. These films were a celebration of Blackness, rather than a mockery of it, offering an on-screen visibility that allowed audiences a better understanding of the many facets to be found in that lived experience.

Although strides were being made, however, Hollywood’s inherent racism persisted, and a few decades later, we got the Blaxploitation Era, filled with low-budget movies that featured outlandish narratives about drug dealers and gang culture. This was a short-lived, but groundbreaking time, as these films were created by Black artists, bent on turning these racier characters into the heroes of their stories, even if it meant uplifting a more negative and violent view of their community. This type of the “Blackness” was more palatable for white audiences, which introduced an intriguing conundrum, one which Jeffrey Wright’s character in American Fiction encounters himself: “Is it okay to give the (white) people what they want if it sacrifices your own morals and sense of dignity to do so? Can a Black artist make a buck or two off of racism? Is that a sort of empowerment or just a betrayal of one’s community?”

The answers to these questions are not simple, and it is in that complexity that true brilliance and understanding of the human condition lies. Rather than giving a watered down, easily-digestible response, filmmakers, screenwriters, novelists, playwrights, musicians, and poets have spent decades using their unique creative talents to excavate this query.

I’m going to place Cord Jefferson, and consequently Monk himself, in the company of three other geniuses: Keenen Ivory Wayans, Robert Townsend, and Jordan Peele. These are writers who use humor and wit to brilliantly comment on and subvert racial stereotypes.

In I’m Gonna Git You Sucka, Wayans parodied Blaxploitation films, highlighting the ridiculous tropes in the genre and showcasing just how silly and unrealistic they are. In Hollywood Shuffle, arguably the closest film to American Fiction in terms of theme and plot, Townsend played a struggling actor who finds his big break as a Blaxploitation star. And, more recently, with Get Out, Peele won an Oscar and left a permanent stamp on the entertainment industry, as he used comedy and horror to comment on race relations in America. And he has only dug deeper into this multifaceted topic with each project he’s produced since.

At its core, American Fiction is a film about relationships – familial, romantic, and professional – and how those dynamics, along with societal expectations, form our sense of identity.

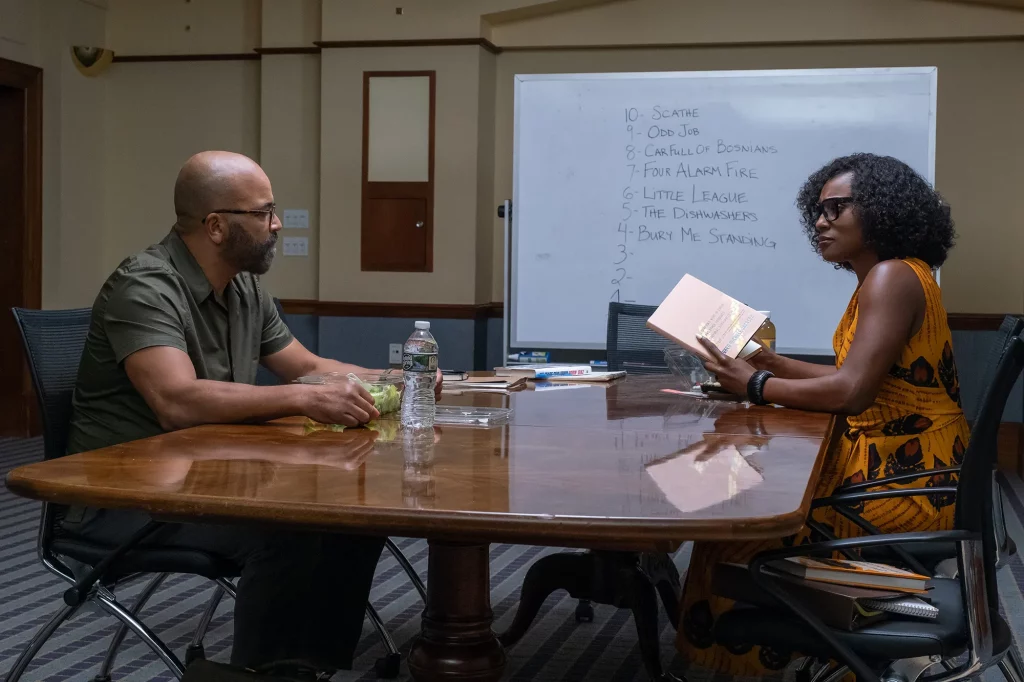

Thelonious “Monk” Ellison (Jeffrey Wright) is an academic, who prides himself on being eloquent and holds himself to a higher standard, and the novels he writes echo this determined sense of purpose. He scoffs at the success of Sintara Golden (Issa Rae), who he believes has sold out by leaning into a less sophisticated representation of Blackness in her work.

Even as his books struggle to retain an audience, Monk digs his heels in, refusing to change his stripes and sacrifice his morals. Until one fateful night, when he decides to write a new story, utilizing every Black stereotype that he loathes to create a novel that he finds absolutely ridiculous. He hands it into his editor to try and prove a point, and is flabbergasted when it starts to gain traction. Now, Monk has a decision to make: Does he stay true to himself and the image he has built, or does he dance with the devil? At first, he tries to have it both ways, using a pseudonym (Stagg R. Leigh) for the new book; but as the book’s popularity skyrockets, the ruse becomes more and more difficult to maintain…

One of the things I find the most intriguing about this particular film, especially when I examine it next to its predecessors in this sub-genre, is that the narrative is less interested in answering the question: “What is the right way to be Black?” and more intent on showcasing the ways in which Black artists and creatives have to contend with the supply and demand of white consumerism.

Both Monk and Sintara are catering to the market, and that market determines which types of Black stories and characters are palatable. There was an intentional visual motif in the film showing how the majority of the readership, particularly the readers who ardently supported the problematic novels, were white. That commentary was both subtle and in your face in all the right ways, pivoting the conversation away from the pressures of disappointing one’s community, and instead refocusing the lens on the core issue: How white peoples’ narrow view of Blackness influences media, especially when we live in a capitalistic society.

I’ve decided to make this a spoiler free review, mainly because I want everyone to see this film and experience the brilliance of Jefferson’s work firsthand. But also because the point of the film is not the conclusion that the characters reach. It’s the conversation that is ignited, both within the narrative and after viewing. This is the kind of movie that will be on the syllabus for courses that study the impact of art on society. It would absolutely have been taught in my African American Cinema class, had it been released at the time. We would’ve had some insightful discourse on Monk and the journey he embarks on toward understanding his own biases and assumptions.

And that is the beauty of the film. Sure, it’s funny, and the entertainment value will ensure a larger audience. But more importantly, it’s poignant, and Jefferson slips some deep and meaningful exchanges in between the humorous and heartfelt story beats.

Whether you intended to or not, you will come away from the experience having learned something about our society and its prejudices. And you may have unwittingly unpacked a few of your own personal biases in the process.

Related lists created by the same author

Coverage from the Austin Film Festival, highlighting some panels and films that emphasized the importance of diverse and inclusive storytelling.

Related diversity category

Related movie/TV/List/Topic

A throwback to the last months of the 20th century in this comedy film.