Snow White, Rewritten in a Minor Key

Despite the film’s efforts to reframe its heroine with modern complexity, a certain emotional distance lingers.

Incluvie Foundation Gala - Learn More

A.K.A. White Men Being Gross

Finishing Tiger King on Netflix can feel like a letdown. What do you watch for the rest of the quarantine? How do you find more things to binge? What about your needs? Other documentaries feel so tame after the dumpster fire flamboyance of Tiger King. There seems to be no way to capture that lightning in a bottle again. Fret not: here are three movies to satisfy your deepest, darkest desires for white men of questionable moral character.

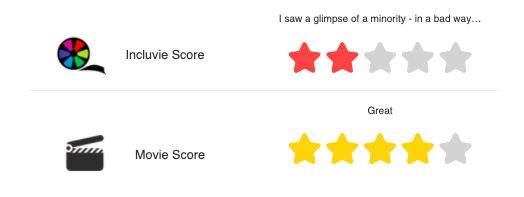

The premise of the 2015 documentary Finders Keepers should be enough to draw in anyone who can’t get enough hillbilly melodrama. In the deep south in the early 2000s, one man bought a smoker grill at auction, took it home, and discovered it contained a human foot. The owner of said foot wanted it back, and a lengthy legal battle ensued.

Finders Keepers is full of that ridiculous, train-wreck, can’t-look-away quality that made Tiger King such a hit. We have our “villain” in the form of Shannon Whisnant, the man who bought the grill and found the foot. Shannon is a man with money on his mind and a nose for what the public wants: spectacle. He immediately starts a “foot grill” website, sells “foot grill” tee-shirts, and hawks tickets to see the human foot in the grill. All of which catches the attention of the foot’s “biological owner,” John Wood, who wants it back. John had lost said controversial foot in a plane crash that killed his father. John had the idea to turn his amputated foot into a memorial to his dad (as you do), but life is never that simple. He makes some bad choices that lead him down a dark path that will eventually find him addicted to drugs, estranged from his family, and homeless, thus leading to the auctioning of his possessions from storage.

Everyone in this movie is white. Most of the ‘cluvies are the women in Shannon and John’s lives: mothers, wives, sisters, and a niece. While the movie centers on the two men and their years-long legal battles, much sympathy is given to the women who are forced to endure life alongside them. John’s life choices force his mother, Peg Wood, and his sister Marian Lytle, to cut him out of the family. By the end of the movie Shannon’s wife Lisa has just about had it with his obsession and mentions on-camera that they are talking about divorce. The film does an excellent job of giving these women a platform for expressing how these two men have turned their lives completely inside-out.

As an amputee, John qualifies as a ‘cluvie, but don’t pity him. Even before he lost his leg in that plane crash, he had made some questionable life choices. During the legal process, he continues to spiral down into heavy drug addiction, eventually losing everything and living under a bridge. It’s hard to feel sorry for him. However, he makes no excuses for his past behavior, and it’s a welcome uptick in the movie’s tone when he finally gets help and starts a sober life.

So, who ends up with the foot? You’ll have to watch and see.

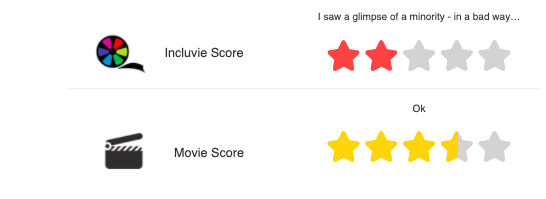

Netflix’s 2017 documentary Voyeur starts as a straightforward documentary that follows iconic writer Gay Talese as he spends 30 years with self-proclaimed voyeur Gerald Foos. For three decades Foos ran a motel in Colorado, which he bought and renovated specifically to cater to his voyeuristic needs. Knowing that Talese was a journalist who loved a good story about sex in America, Foos contacted Talese in 1980, and they began a long relationship meant to culminate in the 2016 release of the book, The Voyeur’s Motel.

Even their strange friendship had been the entire movie, it’s already pretty intriguing. Instead, it turns itself inside-out, twists the narrative, and ends up a messy clash of gigantic egos.

Voyeur is as much about Talese as it is about Foos. Foos’s voyeurism is merely the springboard from which a whole other tale unspools. He produces immaculately kept journals of his time spying on his motel guests, but some quick fact-checking proves that at least some of his dates are wrong. In fact, he may have even used the murder of a young woman in another town to embellish his journals. Talese, writing both his book and an article for The New Yorker, makes an enormous deal of telling us about the remarkable fact-checkers at the magazine, yet several of Foos’s claims manage to fall through the cracks. As soon as The New Yorker publishes their piece, Foos falls apart and tells us he feels betrayed by some of the things Talese revealed — all things that Foos proudly shared with Talese and with the documentary crew. Later, when the book is released, a team from The Washington Post confronts Talese with several factual inconsistencies. Talese goes into an immediate rage against Foos, the documentarians, pretty much everyone except himself. For all that Talese spends the movie humblebragging about his journalistic integrity, it’s clear he cared more about telling a salacious, titillating story than in checking the facts from his single, already unreliable source.

As in Finders Keepers, this film centers on the white men who can’t stop tripping over their egos no matter the cost to everyone around them. Foos’s long-suffering wife, Anita, is painted as a blank slate who only occasionally steps in to save Foos from himself. Talese’s time at a sexually liberated nudist colony in the early 80s is brought up concerning the problems caused by his marriage. Talese’s commitment to embedding himself into his stories, then, seems to be a flimsy excuse for him to satisfy his own sexual needs.

Several other similarities between Foos and Talese are highlighted throughout the film, from their hoarding tendencies to their record-keeping, to their self-aggrandizing decor, and their pride in being “voyeurs”, with Foos in the literal sense and Talese as a journalist. Their relationship is based on co-dependence and mutual self-delusion until Foos’s stories start to unravel; when that happens, it’s every egomaniac for himself.

One thing Voyeur never does is explore Foos’ wrongdoing in spying on unsuspecting guests. The word consent never comes up, nor does the film ever attempt to discuss the topic with regards to the privacy of Foos’ guests. He glosses over his crime under the guise of research and observation of the human condition, even while he admits that he specifically sought out guests engaged in sexual relations. He thinks of himself as a student of the human condition, not unlike Talese. Foos’s first wife Donna, and then his second wife Anita, not only passively accept what Foos does, but they seem encouraging of his behavior. If there’s anything in it for them, the film never explores that, either.

Voyeur is a fun film if you want to see two old white men explode at each other; otherwise, it’s mostly a disturbing look into how white men like to forgive each other for their sins while everyone else is left behind in the mess.

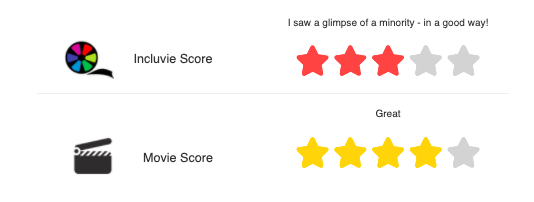

If you thought Tiger King was too optimistic and cheerful, Tickled will surely disavow you of your remaining faith in humanity. What starts out as New Zealand journalist, David Farrier’s curiosity about something called Competitive Endurance Tickling quickly spirals into an investigation of one person’s sick scam to blackmail young (white, heterosexual, able-bodied) men into obedience and silence.

The tickling videos may seem silly, but for the young men recruited to make them — sometimes while underage — their participation is only the beginning of a long battle against an unseen but vicious entity who preys on the poor and vulnerable. Most of the men were recruited when they were very young and financially insecure through the promise of easy money, only to discover their films being advertised online using the same methods and language as porn videos. When the men contact the sites to have their likenesses taken down, they are almost instantly met with threats of lawsuits and exposure, as well as threats against their families.

As a counterpoint to the film’s mysterious antagonist, we are allowed a brief glimpse into one tickle fetishist’s more above-board world of movie-making. He seems like an ok guy who just really likes tickling others and doesn’t appear to lie to his ticklees or blackmail them afterward.

Farrier is gay, a fact brought up in explicit and derogatory terms at the film’s opening. Aside from Farrier, Tickled contains few, if any, women, people of color, disabled bodies, or other members of the LGBTQIA+ community.

The film is well-made and worth watching. It’s empowering to see Farrier brave lawsuits and threats to bring down the big bully. The person behind all of this is so cruel that his terrified stepmother warns Farrier against him. There’s a message to be had about trusting people you never meet face to face, as well as the permanence of the fingerprints we leave online.

Original “Tiger King”- Recommendations published by Meredith Morgenstern on Medium

Related lists created by the same author

Despite the film’s efforts to reframe its heroine with modern complexity, a certain emotional distance lingers.