Netflix’s ‘The Old Guard’ is an Entertaining Flick

"The Old Guard" doesn't break ground, but it sure does bust boredom and fictional heads as an entertaining action romp on Netflix.

Incluvie Foundation Gala - Learn More

We find ourselves in the month of Ramadan, an opportune time to celebrate the work of a Muslim filmmaker: Marjane Satrapi. I decided to re-watch her magnum opus, Persepolis, and was struck yet again by its beauty. First a graphic novel by Satrapi, the story recounts her life growing up in Tehran during the Iranian Revolution. The powerful storytelling shines with poetic animation, an exploration of deeper truths, and highlights the protagonist’s complex search for identity. All of these elements give Persepolis an enduring beauty and make it a film worth coming back to time and again.

Different aspects of the animation hold meaning and thought behind it. The use of the fantastical puppet-like imagery to depict historical facts borrows from the ancient artistic tradition of Shadow Theater. When we see young Marji’s (a pet name for Marjane) uncle recounting the political rise of the Shah (whom we now know was backed by the American and British governments for economic interests) the puppets dance and we see the retelling of history through the eyes of a child’s perception. In other words, Persepolis not only uses the ancient tradition of Shadow Theater to recount historical tales in a sort of “homage to the past” kind of way but also brings us into the childlike interpretation of a younger Marji’s imagination.

There is also a lot of imagery or symbolism superimposed with grave depictions of war and violence. An example of this is when rioting silhouettes turn to complete darkness so as to suggest death rather than blatantly show us. In a similarly nuanced scene, one of Marji’s friends narrowly misses the neighboring roof he tries to jump to and falls to his death after being chased by armed soldiers. Instead of showing the fall, the moon behind the building becomes the central focus, with the subtle downwards look of the soldiers as the only scenic indication of his death.

One aspect I haven’t yet addressed is the poetic use of black and white animation. Its power stems from the double meaning it represents. On the one hand, the usage of black and white is a clever tool to dissociate from the present-day storyline (which is in color). On the other hand, it echoes the ever-present moralistic duality and the strict dichotomy between right and wrong that plagues a post-Revolution era Iran. This is clear when a zealous man chastises Marji’s mom for having hair poking out of her veil. Though in his eyes he sees her blasphemy as a sign that he has the moral high ground, he then disrespects her, calling her insulting expletives. This Manichean approach is fundamentally flawed, as few things in life fit into either right or wrong, which makes room for unjustified hypocritical moralism. On a similar note, Marjane later speaks out against men’s absence of vestimentary restrictions in the context of sexual liberation in women. “Don’t you think men wearing tight pants won’t turn us on?” she asks a board of teachers and administrators who are enforcing an even more strict sartorial policy on the women. Hypocrisy is an injustice Marji deals with continually.

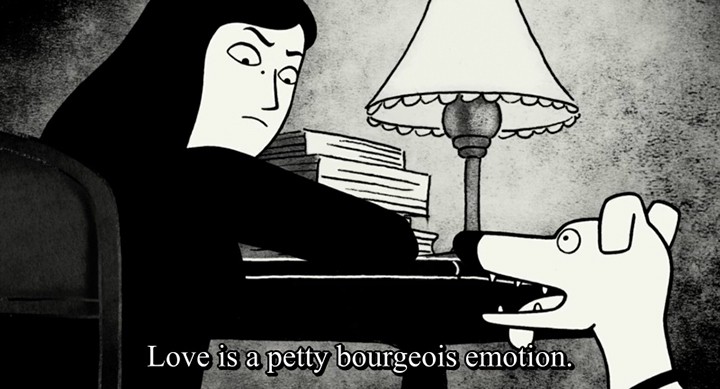

When Marji moves to Europe for her safety at the behest of her parents, she is greeted with a whole new set of circumstances. The friends she makes at first seem like liberated free thinkers who share a similar communist and anarchist ideology to her. They show Marji the philosophy of “Nonchalance” and the alternative punk subcultures of Vienna, and express great interest in Marji’s story and how she survived a bloody revolution. They seem woke, progressive, and yet, in an ironic twist of fate, when discussing Christmas plans, they complain about having to travel to Brazil or other such fancy destinations. They relate their struggles to her as if they were of equal magnitude. Though they talk a big game, the hypocrisy of youth stands out and their oxymoronic and convenient proletarianism belies their privileged and sheltered nature.

When she falls in love for the first time, Marji unconsciously puts on rose-colored glasses. Harp music plays in the background, we see lovely scenes of nature, walks in the park, innocent flirtation, and idealizing—until, that is, she finds him in bed with someone else. Post break-up, her memories start to comically change, recalling instead the not-so-pretty reality of her first boyfriend. He takes on a more cowardly personality. Suddenly, he has acne and an endless supply of mucus, and he hides behind Marji during difficult situations. The deeper truth shown here is that first love is often romanticized. But the realization of her relationship’s beautification is done in a humorous fashion.

Another subtle theme Persepolis puts forth is humor in the face of adversity. Marji buys a misspelled jacket that says “Punk is not Ded” at a time when items from the West are banned and cheekily covers her tracks when she gets called out for it. Her psychologist makes doodles instead of listening to her problems. “Eye of the Tiger” plays as Marji battles depression. In lieu of the usual montage that shows the progression of physical strength, it shows her getting her life back together (showering, waxing her legs, singing the song off-key, going back to school etc…), and that ties into another big aspect of the film, the search for her identity.

At a young age, Marji believed she was destined to be a prophet. She even had conversations with God, which changed into conversations with God and Karl Marx later in her life. That perhaps bled into her relatable struggle of not fitting in and her conflicted and complex relationship with religion. For Marji, not fitting in is expressed through how she feels closely tied to the West while in Iran, but misses it when she finds herself in Europe. She doesn’t quite feel at home in either; an outsider in Austria, and coming back to an Iran that’s unrecognizable to her. In terms of religious expression, she is at odds with the switch to a fundamentalist regime that believes piety is the only way. This is echoed in her attitude, while in Europe, at being housed by nuns who also have strict ideas that Marji opposes, which has to do with her contempt of authority. This contempt melts away with the authority of family figures. Marji bases a lot of her decision-making on the values of integrity and honor instilled by her grandmother who is a sweet, caring, and wise figure in her life. Marji carries with her, all throughout, this grace and resilient mentality that she inherited. It is fitting that the movie ends with the jasmine petals falling down, the same ones that were used daily by her grandmother. A touching end to a beautiful movie.

Satrapi, no need to worry. You made your grandmother proud.

On the Incluvie scale, this is definitely a 5. Positive Persian representation is often overlooked in cinema, usually veering to the harmful. The director is a woman and this is a female-driven story. It highlights women’s issues around the world and the dangers that can come with feminism and sexual liberation. It shows activism within political instability and much more. Persepolis treats issues of identity, religion, double standards regarding gender, and culture shock with great subtlety, impact, and beauty.

(This article was originally published by Mick Cohen-Carroll on Medium.)

Related lists created by the same author

"The Old Guard" doesn't break ground, but it sure does bust boredom and fictional heads as an entertaining action romp on Netflix.

Related diversity category

The film follows the biblical story of Moses, from his time as a prince of Egypt, to a leader for the people of Israel. It’s a film that works brilliantly in animation, and is one that both children and adults can; enjoy despite its religious contexts, it is friendly to general audiences.