'You People' is as Glossy and Uneven as its Predecessors

Another uneven "Guess Who's Coming to Dinner" redux that says nothing novel about its subject matter.

Incluvie Foundation Gala - Learn More

The Black Phone is a combination of cinematic tropes that work on an intuitive level. The film’s source material is Stephen King’s son, Joe Hill’s horror short story, The Black Phone. Director Scott Derrickson (Marvel’s Dr. Strange) combined the 30-page horror short story with his childhood traumas, anti-nostalgia bent, and an impressive Ethan Hawke in his first villain role. The result is an atmospheric movie that assures doom to viewers while cruelly delaying the inevitable.

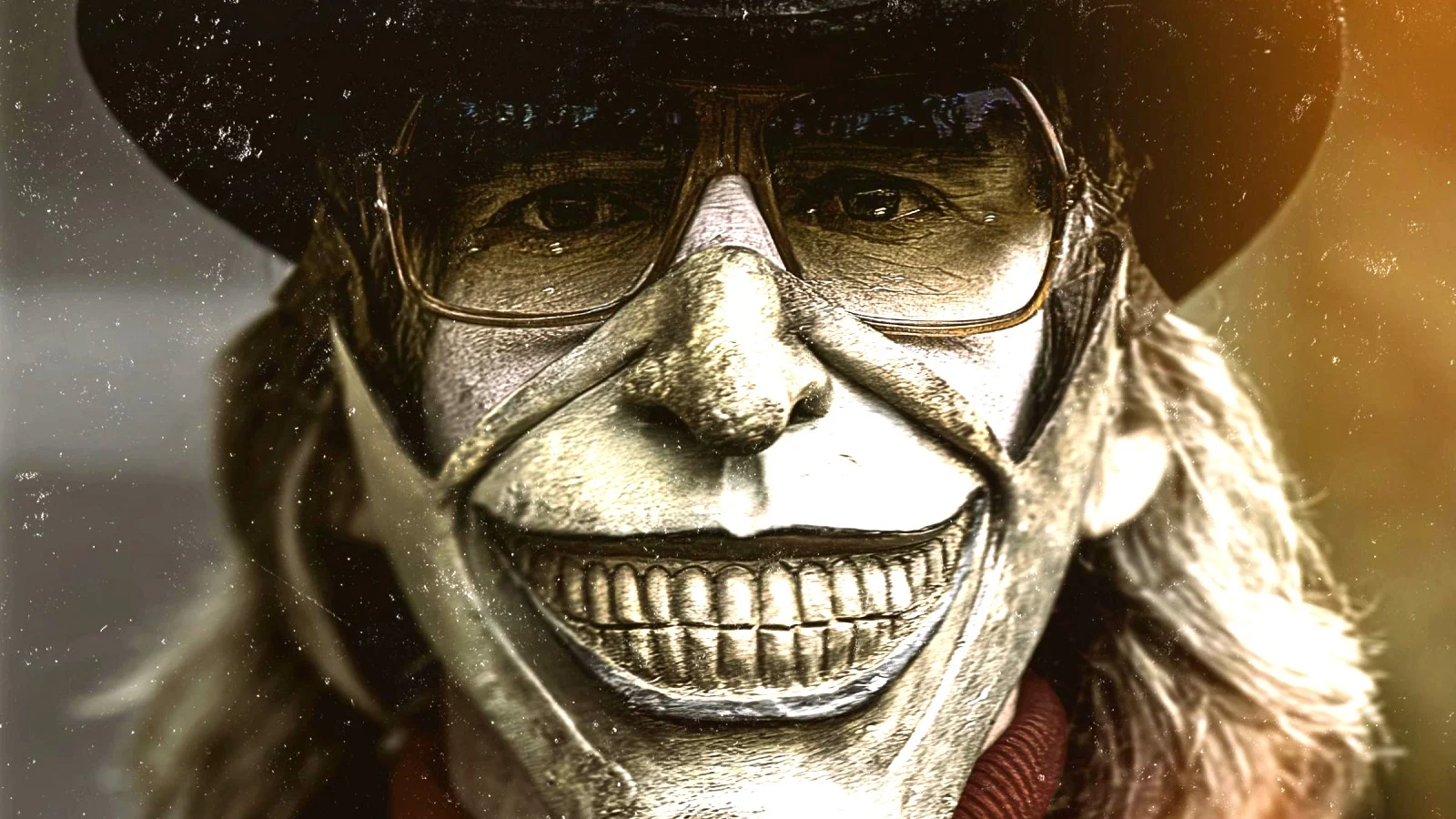

Derrickson relayed that he used his childhood trauma (trauma that has taken him 3 years of ongoing therapy to come to terms with) to inform The Black Phone. The storytelling revolves around a serial killer known as ‘The Grabber’. He is abducting and presumably killing teenagers in Denver, Colorado. Our protagonist is 13-year-old Finney Shaw (actor Mason Thames), who gives us a childlike view of suburbia in the 70s. Derrickson stays true to his convictions, showing the less sparkly sides of childhood. He refuses to engage in glamorizing the past, even stating, “Bob Dylan said, ‘Nostalgia is death,’ and I tend to agree with that.” There are bullies everywhere, a deceased Mom, and an alcoholic father who beats Gwen for being too much like his late mother. Not to mention, the father gets no real comeuppance, a sad reality for many that Derrickson speaks to through his film and characters.

Derrickson gives us suffocating chain link fences, overcast skies, and the omnipresent threat of unchecked abuse both in and outside Finney’s home. The director never lets up on the foreboding atmosphere, increasing the tension steadily by keeping a grey, unfeeling world in constant contrast with the fleeting happiness between Finney and his sister, Gwen. Derrickson mostly aims for realism in his film technique, showing conflicting images. Gwen and Finney’s relationship, being symbolic of siblings enduring an abusive, alcoholic father, school bullies, and grief over a deceased mother, is one of closeness. This makes Finney’s eventual abduction even more heart-wrenching. Derrickson employs this emotional bombing in several relationships. For instance, Robin befriends Finney and saves him from his bullies. We are introduced to him demolishing a bully’s face and soon learn that he is a trained fighter… only for the following sequence to show him being ambushed by ‘The Grabber’. This move could feel cheap in a less capable director’s hands, but instead, we feel even more inevitable doom when ‘The Grabber’ abducts Finney in the inciting incident. What hope can our frail protagonist have if his guardian was no match? This is the quintessential question that the film centers on.

The film is a masterclass in knowing what to show and not show. I am reminded of Colin Trevorrow and Zack Stentz’s Jurassic World: Camp Cretaceous’ use of off-screen space and misdirection to get around humans becoming lunch for genetically modified dinosaurs in a show aimed that younger audiences. Derrickson employs a similar understanding, never actually showing any kids brutalized on-screen. Make no mistake, there are uncomfortable scenes showing Finney distressed during violent struggles and the victimized teens before his abduction. Derrickson stated, “[t]here were things in my childhood that were too dark to put in… I think you have to have a sensitivity of what an audience can tolerate without really being turned off or turning on the film itself.” Like the best docuseries, the director gives us enough of the enactment to make us horrified, without pushing us into undesired child torture-porn territory. Instead, Derrickson keeps the focus on childhood resilience.

Derrickson also preys on audience fears. Despite the conflict here being character versus character, without explicit violence being inflicted, I found myself looking away from the screen several times. This is an uncomfortable film that forces you to confront your fears. When we watch a 13-year-old boy who has already survived so much, be abducted, we are confronted with our fears of a crapsack world. A world where horrible things can happen to the most innocent of people. The mise en scène of Finney’s dungeon is genius. Watching Finney be tossed on a filthy mattress on the floor activates the exact repulsive feeling you are fearing as you read this sentence. When Finney’s voice breaks as he tries to tell ‘The Grabber’ that if he “touches him”, he’ll scream and scratch his face is as shattering as it reads. Hearing ‘The Grabber’ tell him that he wants to play ‘Naughty Boy’ and hack him into small pieces with a delightful giddiness, will upset many viewers. The setting is a filthy basement, soundproofed, and squat, with a barred window cruelly just out of reach from Finney. Even crueler still, a black phone hangs on the wall, disconnected from the world. ‘The Grabber’ meant for it to be a torturous symbol, but Finney will come to rely on it for its connection to another world.

You will feel your heart shatter as Finney screams, cries, and pleads to be released. You will feel the film’s grip on your throat as ‘The Grabber’ closes in, teasing that he will torture Finney for being “special” and “not like the others.” You will feel all of this while never witnessing a single child attacked by ‘The Grabber.’ Your reward will be a climactic finish that sees justice finally being a friend to the kids in this cinematic world. This is a movie that combines a ghost story, revenge tale, and serial killer obsession into a cinematic experience that uses your fears against you. We should be thankful that Derrickson dropped out of directing Dr. Strange & The Multiverse of Madness, and instead filmed this excellent addition to the horror and thriller canon.

Related lists created by the same author

Another uneven "Guess Who's Coming to Dinner" redux that says nothing novel about its subject matter.

Related diversity category

A story of a magical dragon brings great representation for Chinese culture.

Related movie/TV/List/Topic

"13 Going on 30" tracks the tricky transition from adolescence to adulthood.