‘Good Will Hunting’ is Good to Watch for Mental Health Month

The relationship between Will and Sean is the best part of the movie. It’s always a delight to see Robin Williams on screen

Incluvie Foundation Gala - Learn More

As Ammonite and Supernova enter theaters and get their VOD releases, audiences are given their annual taste of queer cinema for the winter awards season. And once again, as it was in 2005 when Brokeback Mountain was dominating the Oscars conversation, what few queer-themed films that are released continue to star mostly heterosexual and cisgender actors. As a gay man, I have to wonder why this keeps happening so often, decade after decade. And I must be clear, I am first in line to praise Cate Blanchett and Rooney Mara’s powerful performances in Todd Haynes’s Carol, and I do think films like Philadelphia, Milk, Call Me by Your Name, and Brokeback Mountain are worthy of the accolades they receive for their writing, directing, and acting. But I do have to wonder, would these films feel more truthful, or at least more emotionally rich, if these gay characters were actually played by gay people? It isn’t as if there’s a shortage of highly skilled working gay actors, there are certainly trained LGBTQ+ performers out there who struggle to navigate an unequal system.

In a 2020 GLAAD study, of the 118 films counted from major film studios in 2019, 22 (18.6%) contained characters identified as LGBTQ, showing a slight improvement of two films from the previous year’s 20 films (18.2%). GLAAD also reported that the racial diversity of LGBTQ characters decreased to only 34% of LGBTQ characters being people of color. Of these few characters that are identified as LGBTQ, most were portrayed by otherwise successful heterosexual actors (such as in Rocketman, Booksmart, and Velvet Buzzsaw). What if an unknown gay actor played Elio in the high-profile Call Me by Your Name and received an Oscar nomination for his breakout performance, instead of chiseled Tumblr-boy dreamboat Timothée Chalamet? In the massively successful Rocketman, instead of hunky Taron Egerton playing the most muscular version of Elton John ever, what if a gay actor who fits Elton John’s description a little better portrayed the gay icon? Would Ryan Murphy’s The Prom not benefit from replacing James Corden’s arm-flailing, gay-lisped performance with someone like Tituss Burgess?

When a straight actor plays a gay character, it is devoid of any potential authenticity — it is a projection. Some actors will draw from stereotypes and “play gay”… whatever that means to them. Many people would argue that “they are just acting”, and “that is their job, as actors, to replicate truth”, but these arguments don’t change the fact that hardly ever do LGBTQ+ actors get the opportunity to play these types of roles in the first place. There are certainly gay, lesbian, and bisexual actors who have been successful portraying heterosexual characters, but it is not the same issue the other way around because of how many heterosexual and cisgender roles are available in comparison.

Most major film studio executives will not include LGBTQ+ characters in their films out of fear of backlash with international box office success. They see inclusivity as too big of a risk to take when releasing their films to anti-LGBTQ countries. As a result, audiences receive representation in the form of that two-second-long gay Le Fou moment from 2017’s Beauty and the Beast, or that one-scene-long gay role in Avengers: Endgame played by one of the film’s straight directors. Queer people are minimized to these blink-and-you-miss-it characters. Ramin Setoodeh and Elizabeth Wagmeister of Variety said it best;

“There are no openly gay or transgender characters in most of the major studio film franchises — from Jurassic World to J.K. Rowling’s Fantastic Beasts. And while coming out has become easier, there are still scarcely few openly gay or lesbian movie stars on the level of a Jennifer Lawrence or a Chris Pratt.”

If any LGBTQ+ actors were considered “internationally bankable”, this would not be the issue it is.

Transgender and non-binary performers and characters have been, by far, the most underrepresented group. According to GLAAD’s 2020 study of 2019 films, there was zero representation of transgender and non-binary characters in any major releases, which was consistent with the previous two years. Transgender activist and actress Laverne Cox states,

“If you don’t hire us to work, we’re never going to become that big name. It becomes the thing where we don’t get the opportunities, and then we can’t become bankable internationally. I think it’s about taking a moment to cast a trans person in something that’s supporting and have us prove ourselves.”

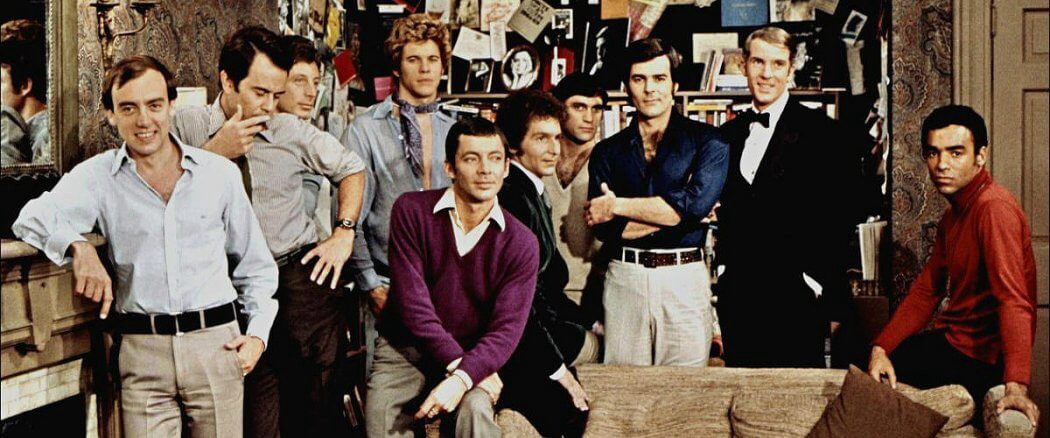

The 1970 William Friedkin film The Boys in the Band (based on the play by Mart Crowley, who wrote the screenplay) was groundbreaking because of its entirely homosexual cast. The Ryan Murphy-produced Netflix remake released last year honored the original by doing the same, and both films, though vastly different as far as filmmaking is concerned, speak to me more than most gay-themed films because of this authenticity. I am able to connect with each of these men on multiple levels and I can at least understand a measurement of where each of the actors are coming from, because they are gay like me. And throughout that runtime, I feel represented — I feel as though this was actually made for someone like me. This is a far cry from what it’s like to see Timothée Chalamet and Armie Hammer pretending to know what these feelings are. The fact that the 1970 The Boys in the Band is still groundbreaking by today’s standards blows my mind because, according to all those Oscars acceptance speeches from actors like Tom Hanks, Hilary Swank, Sean Penn and Jared Leto, you’d think we would have come much farther by now.

Of queer cinema, the most successful group, as far as representation goes, has been that of white gay men and white gay-themed stories. I can appreciate films like Brokeback Mountain and the difference it made in audience perceptions of gay-themed stories. But can we do better, and keep moving forward? Of course we can. Representation in 2021 is vastly different than it was in 2005, and one could firmly say movies are more inclusive than ever, but how progressive is it if it’s still mostly work done by straight, cisgender people? If studios were serious about diversity and having more LGBTQ+ film characters, subsequently, there should be more LGBTQ+ breakout stars from these films. For every Carol and Call Me by Your Name, there are still solely heterosexual and cisgender actors receiving the praise, the awards reception, and future career opportunities for being “brave” enough to do these films; they benefit from the diversity without actually being a part of it.

I have come to realize that these big studio “queer-themed” movies, for the most part, aren’t really for queer people — they are tailor made to be accessible for the consumption of straight, cisgender audiences. This is frustrating, of course, because everything is for straight, cisgender audiences. Queer cinema should not be treated like a roadside attraction, or an occasional tragic gimmick in between all the superheroes and remakes. Queer cinema should be a boundless, colorful body of work crafted by and for queer people. True artistic freedom is having only LGBTQ+ people create, produce, and star in such stories.

In theory, I really do not have a problem with the idea of a straight actor playing a gay role — it’s just that it happens so often… It happens so often. This happens every year: A gay or queer writer-director has a screenplay that gets made into a major motion picture, the studio hires A-list heteros, a trailer is released with some emotional orchestral music, and the film is given the usual awards season push. When I first saw the trailers for Ammonite and Supernova, all I could think about was how tired I am of this. I’m tired of people saying this issue is “too complicated” or “too radical” to discuss. I’m tired of cisgender actors portraying transgender people. I’m tired of queer people of color hardly ever having their stories told. I’m tired of LGBTQ+ actors not starring in these films that supposedly reflect their reality, while Hollywood A-listers use them as a career-boost. I suppose I should feel more represented than ever, but all I can think about is how there’s all these queer-themed films that straight, cisgender people get credit for. If studios really wanted their films to be more inclusive and more diverse, they would push for more opportunities for more LGBTQ+ people to authentically represent the LGBTQ+ community, both behind and in front of the camera.

Originally posted by Matthew Dorado on January 29, 2021

Related lists created by the same author

The relationship between Will and Sean is the best part of the movie. It’s always a delight to see Robin Williams on screen