'Unsolved Mysteries': Netflix’s Revival Series is as Eerie as it is Compelling

'Unsolved Mysteries' is a reminder that not everyone has closure in their lives. Things will happen that have no known explanation, and seemingly come out of nowhere.

Incluvie Foundation Gala - Learn More

Movies don’t exist out of context, and 2019’s Sea Fever (Prime Video) is no exception. Without our current situation, you could easily categorize this film as simple nautical horror in the same vein as Jaws or the more recent Underwater. It stands up as a fishing boat version of Alien. There’s a touch of The Perfect Storm going on here, as well. However, in April of 2020, Sea Fever becomes an on-point morality tale of quarantine, isolation, helplessness, and hubris. The last third of the movie is so spot-on it’s eerie.

Once you get past the awkward opening address that feels like you’re watching Sea Fever at a science center, the film makes sure we know without a doubt that the main character, Siobhán (Hermoine Corfield) is not a people person. She tells us: “I don’t do joining in.” Thanks for spelling it out! She books herself passage onto a fishing boat so that she can study their catch for some MacGuffin-like reason. The boat is run by Gerard (Dougray Scott) and Freya (Connie Nielsen), a longtime married couple who are just the right amount of salty and craggy to make them interesting but personable enough that you don’t hate them. Siobhán, whom we have established doesn’t “do joining in” (in case you already forgot), keeps herself separate from the crew, who have worked together for a long time and enjoy hearty laughs and good-natured ribbing with one another. While plotting their course, Gerard and Freya are told to go around an “exclusion area” of the ocean. Gerard promptly ignores this directive because the exclusion area has a large shoal of fish to catch; he’s a dude, this is his ship, and their livelihood rests on a big catch. Thanks to Gerard and his bad-boy behavior, the ship gets stuck. Blue goo also appears in the walls of the lower decks. Siobhán, as a scientist, is called upon to figure out the goo situation. Like any respectable, well-established scientist, she touches it without gloves and plops some down in a petri dish without sealing off the area. The goo, it turns out, comes from a much larger creature that has the ship caught in its grip of thin tentacles that honestly look like super-sized, glowing blue worms. Gerard takes his self-loathing out on Siobhán, who is sent diving into the water to scrape the goo/barnacles off the ship. She gets spooked by a giant creature with a ton of mouths and refuses to go into the water again. With a few nautical tricks, Freya and the crew manage to free the ship anyway and get moving again. However, it is belatedly discovered that the goo contains tiny parasites that enter into human bloodstreams and cause fevers, eyeball explosions, lacerations, and other unpleasantries. Now the moral dilemma arises: bring the ship back to port to seek help, or quarantine themselves at sea until they can be certain that they’ve disinfected the ship and no one else is infected?

The moral of the movie may seem clear to most of us during these uncertain times — stay away from others until you figure this situation out. You don’t even need to be in the middle of a global pandemic to understand that one simple thing; clearly, the crew has never seen Alien. Freya thinks that getting everyone to a hospital is their only chance of survival, and it’s hard to completely dismiss her logic. If you don’t know what this is, and nothing you do seems to kill it, then shouldn’t you put everyone in the hands of experts? Siobhán, as the representative for the entire scientific community, argues that these are the very reasons why they should self-quarantine: because they don’t know what this is and they can’t seem to kill it.

Ultimately the movie boils down to reason vs emotion. While everyone knows that the scientist is right and that they should do the responsible thing, the crew’s emotions are running high after several bloody deaths; understandably, not everyone is in the mental state to cool off and behave rationally. Fear is nearly always going to override logic. Tragically for this crew, fear begets bad decision-making which leads to more deaths and, potentially, spreading the parasites to everyone back on land.

Siobhán remains clinical and cold to the very end, to the point where you might wonder if she falls somewhere on the spectrum. Halfway through the film, she manages to bite the bullet, sort of becoming part of the team because they need her. One scene shows her almost hooking up with a crew member, but they are interrupted before their first kiss (based on what happens a few minutes later, she actually dodged a pretty gross bullet there). It’s not her job to be a joiner or to make friends; her disposition will help her put logic ahead of fear at the very end.

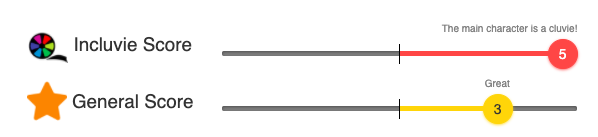

Sea Fever passes the Bechdel Test without feeling forced; with three women in the film, including an older woman who throws a mean left hook, and two male crew members of Color, Sea Fever easily scores high on the Incluvie scale. As the captain, Gerard starts off as a typical “I know better” white male but takes himself down a few pegs when faced with the consequences of his selfish decisions. If only he had stopped to think and listen to the women before making those decisions, he might never have brought this mess upon them; at least he shows remorse.

The dangers of ignoring science in the face of overwhelming evidence is not a new theme. What Sea Fever says here is that sometimes (maybe oftentimes) the right thing is also very, very hard — not everyone can handle that. Even those who listen and pay attention aren’t always going to be rewarded.

Original Movie Review published by Meredith Morgenstern on Medium

Related lists created by the same author

'Unsolved Mysteries' is a reminder that not everyone has closure in their lives. Things will happen that have no known explanation, and seemingly come out of nowhere.