What is the meaning of life? For centuries, philosophers have been trying to find the answer of this ever recurring question.

In 1955, a name tried to answer this. A name which would become familiar across the seas, a name whose works would be studied for decades to come, a name which would inspire the likes of Scorsese, Lucas, Coppola, Kurosawa, Kazan, Nolan, a name which would be remembered for ages in retrospect. A name which would demand respect.

I remember my older cousin asking me who my favorite writer was when I was 9. I had read nothing but course books in the name of literature, but, without any hesitation, I answered him “Satyajit Ray“. There was a 2-part short story written by Ray in our English book about a magician and his parrot. Today, I still haven’t seen as many films as I’d like to, but I say, without any hesitation, Satyajit Ray’s Pather Panchali is one of the best films ever made.

Imagine a debutant director, just 8 years after India’s independence, making this film in challenging times. Now, imagine it getting a BAFTA for best picture from the very people that colonized India. Not that BAFTA is a measure of whether a film is good or not, not that Satyajit Ray needs a BAFTA, but the fact that the same people whose only argument of ruling over India for centuries was that it couldn’t function without them, were now acknowledging the art of the country that they left in a (excuse my French) shithole.

Because the film is set in Bengal, I would tell you a story about the British invasion of Bengal that haunted me as a child. Bengal used to be world’s leading exporter of textiles. In order to destroy the textile competition from India, the British started lowering the prices of exported textiles. When even that didn’t work, they started going to every village and destroying handlooms of helpless farmers, and those who dared to repair them were punished by cutting their thumbs off. This was one of the many, countless, innumerable atrocities that the British Raj gifted to India. I might rant about the colonial rule some other time, but not today.

Pather Panchali captured India in a way that very few films have: the authenticity of sibling relationships, the sacrifices of their parents, the passive aggressive taunts of villagers, the disdain of the mother towards her elder in-laws and a breathtakingly beautiful countryside. The joblessness, life expectancy, illiteracy and poverty at the time made day-to-day life seem absurd, and it is the absurdity of life which begs for its meaning.

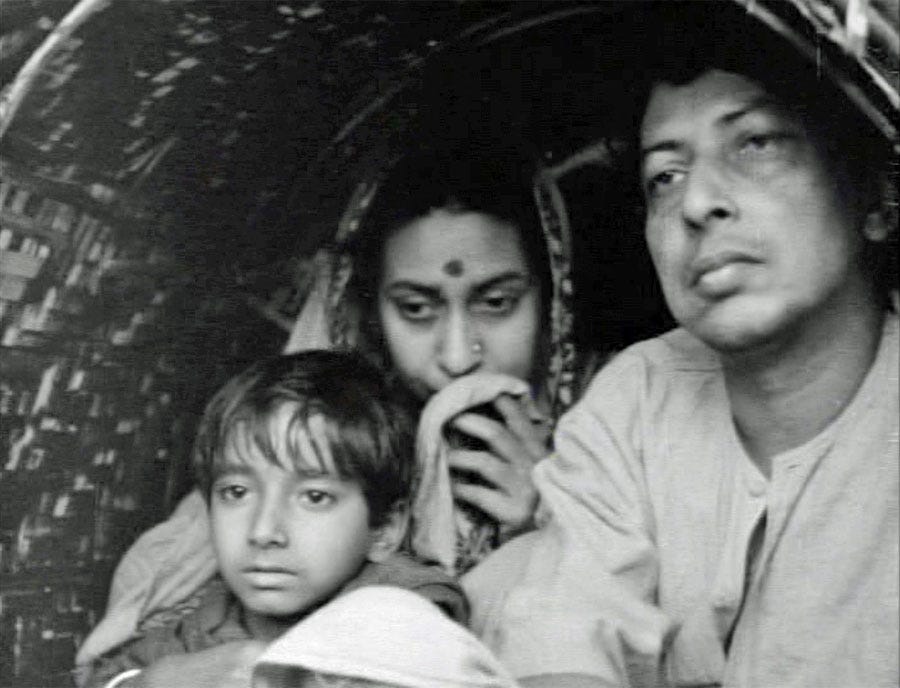

Pather Panchali begins with 4 characters at its center, a young Durga, her mother(Sarbojaya Ray), her father(Harihar Ray) and her old aunt. The Ray family lives together in a temporary arrangement that they have made to repair their broken house. Times are slick for Harihar; he has a degree and is a scholar, he writes way better than his contemporaries who, in his own words “Recycle the same old stories again and again”, but he is not as famous as them. Hence, he works as a daily wage labourer for local farmers, presently out of job.

THE RAY FAMILY

Durga is mischievous. She annoys other villagers due to her habit of stealing. She doesn’t steal jewels or any other expensive commodities, but fruits from other people’s farms, sometimes for herself and sometimes for her old aunt who keeps them stored in a little wooden basket of hers, and that’s why all other ladies in the village taunt Sarbojaya. If there’s one thing that hasn’t changed about us Indians in these 65 years, its that we are all A-Grade hypocrites. When an infant eats other people’s makhan(butter), we find it cute but when this girl does the same, it is annoying. Maybe it has something to do with the fact that we worship that infant, who lived centuries ago according to some manuscripts, and this girl is living right now. Maybe we will start worshiping her some centuries later, who knows? She is afterall, named Durga.

Sarbojaya is a prideful woman. She doesn’t like this constant nagging of other villagers. She does give them back a handful sometimes. Though she unloads most of her frustration on Durga by scolding her left, right and center. This film also deals with loss – I want to prepare you to read about it because I was certainly not prepared to see it in the film through Satyajit’s lens. Philosophers are divided on how they perceive loss. Plato believed that

The body was a prison of the soul and that death was the epitome of freedom.

While Nietzsche believed that

Everything that happens in life will return eternally. Many people, he said, go through life just trying to survive, hoping for a better tomorrow. He said that the secret of living a fulfilled life was to accept and embrace reality and that is a mark of free spirit.

Camus though, projected a very big question. He said

There is but one truly serious philosophical problem, judging whether the life is worth living or not.

You might find it tough to answer Camus. What kind of life is Durga’s family living? A woman as old as Durga’s aunt continuously goes back and forth with all her stuff from one of her nephew’s house to the other’s, a man as intelligent as Harihar works as a laborer, a woman as patient as Sarbojaya has lost hope and a girl as playful as Durga feels left out. Thankfully, Ray answers all of these questions for us.

Durga’s aunt might be hungry herself, but she doesn’t forget to feed the cats; Harihar might be out of work, but he gives Durga money whenever she wants to buy something; Sarbojaya might nag at Durga, but she still defends her in front of others; and Durga might not be liked by her friend’s mothers but she is popular among her friends. Ray takes Nietzsche’s approach to live life. To embrace reality and to find happiness in little things. For life is short and death is inevitable. After all, who has defeated death? Well there is someone who did: Sisyphus.

THE MYTH OF SISYPHUS

Sisyphus is a Greek mythical figure. When Zeus’s king ordered death to Sisyphus, he tricked Thanatos (death in greek) to show him how chains work, trapping Thanatos in chains. The gods became so angry at Sisyphus that they instead punished him to move a boulder up a hill. Just as he would be close to pushing it all the way through he would find himself at the bottom again, hence resulting in the punishment lasting for eternity. This example might seem out of place right now, but just bear with me for a while.

Coming back to Durga’s world again, a new member has joined the family. Apu, Durga’s younger brother. Who knew that every void in Durga’s life could be filled by her younger brother? Durga, though, doesn’t take nearly as much from Apu as she gives. She is strict when the situation calls for it, supportive when Apu wants her, and daring when Apu asks for something. In a beautiful scene, Durga takes Apu to a land much farther away from their house just to let him see a train. This relationship is what I cherished throughout the film. Durga giving Apu a sugarcane to eat, pushing him to get money from their father, running after him, beating him and then making up to him again.

Though Durga is way happier than she used to be, little has changed for her family. Her father went to work in the town where he doesn’t write from and her mother looks worried. Days pass by and their life remains uninteresting. What became interesting for philosophers though, was Sisyphus’s story. Various philosophers gave different perspectives as to what they think was the most remarkable aspect of the story. A man who was so scared of death that he chose to live a life as repetitive as that, what must he hope for while he pushes that boulder, what makes his life worth living, what is worse life or death?

But not everybody is Sisyphus, and not everybody can escape death. Durga’s old aunt is no more. She’s gone just like that, sitting on a rock, as peaceful as death could strike. In a remarkable scene, both Durga and Apu are crying their hearts out sitting at the place where their old aunt used to sit. What I would remember about her was how Ray kept her childhood alive in her, how she used to be the partner in crime of Durga, how she persuaded Harihar to buy her a shawl and roamed in the entire village to show it off.

Sarbojaya asks Harihar to leave their house and take them to Benaras where his friends live. Harihar though, isn’t so sure about that. He agrees that there are more opportunities of work in Benaras, but how could he leave their ancestral home, they’re after all the 5th generations to live in that house. Harihar leaves for town again.

On another usual day, when Durga and Apu are roaming carelessly in the village, it suddenly starts pouring — seemingly as if it’s the first rain of the monsoon. Apu finds a shade under a tree, but Durga is in no mood to stand there, she starts dancing in the rain, enjoying as much as she can, while Apu looks in disbelief at her, scared of his mother’s scolding.There is something astonishing about this scene and something free spirited about Durga. This is the happiest that we’ve seen her so far. Almost as if she has broken all the chains which were holding her back, almost as if she has broken through every prison that was keeping her detained.

Things start to go downhill from here. Ray has suddenly chosen the Shakespearean way of story telling. The look on Apu’s face suggests that something is worrying him. We soon realize that Durga has caught a cold and her mother is doing everything she could to make her feel better. Durga promises Apu to accompany him to see a train again whenever she gets better, to lighten him up.

Rainy season has hit the shores of Bengal as fiercely as ever, Durga is holding her mother as tightly as possible as windows and doors of their un-repaired house bash back and forth. Next, we see shots of outside their home in the morning, the storm of last night has done fair bit of damage to their house. Apu runs to the house of Sarbojaya’s sister in law, the pacing of the film suddenly drops, and Ray suddenly resorts to extremely long shots. “Mother is asking for your help,” Apu says. We see Durga and her mother once again, but this time, Sarbojaya is holding her as tightly as possible. Sarbojaya’s sister-in-law tells Apu, “Apu, please call your uncle,” as calmly as possible. She succeeds in fooling Apu at this moment but not us… not us. For we know what storms mean in a Shakespearean universe, for we know what silence means after a dreadful night. Our Durga is no more…little Durga, mischievous Durga, Apu’s Durga…

LOSING “THE RAY” OF HOPE

Satyajit distances Apu from us for some time by not including a single scene of him for a while, and for that I am thankful. I couldn’t see him grieving for Durga, for my heart could take only so much of pain. I’d like to believe in what Plato said, I’d like to believe that Durga’s soul is now as free as ever, I’d like to believe that she is in a world right now where she’s isn’t nagged for enjoying herself, where she doesn’t need to worry about her marriage, where she could not only see trains but miracles, for she sure was a miracle maker.

Harihar returns from town with a good news. Though he wasn’t able to write, he did get a job. He has brought everyone gifts from his journey. Harihar is describing his experiences in the town to Sarbojaya, while she is holding onto her tears for as long as she could. As he tells her what he has brought for everyone, he shows her the sari that he has brought for his Durga. I wouldn’t write more about this scene because I can’t, nor do I want to. You could imagine what would happen when a mother tells a father about the untimely demise of his daughter, whom he couldn’t even bid a farewell, who is at peace for a while now.

RIDICULING THE CLOUD CUCKOO LAND

Martin Scorsese said:

I prefer the escapism of fantasy, rather than the escapism of incredible sentimentality. What I’m afraid of is pandering to tastes that are superficial. There’s no depth anymore. What appears to be depth is often a facile character study

Ray believed in the same. He rejected the funding of anyone who wanted to change the ending of the film. Films are mirrors of the society. Giving the audience an overly optimistic story at a time like that was something that Ray could never come to terms with. His films reflected the social and political aspects of the society and hence had(and still do) a huge impact on masses. He showed India without a filter: be it Sarbojaya’s different behavior towards Apu and Durga, Durga’s friend getting married at such a young age or Harihar saving money for Durga’s dowry. Ray left activism for filmmaking, but activism never left him. His works commented on the caste system, untouchability, one-upmanship, communalism and classism. His earlier works depicted that society wasn’t ready to accept women as a separate entity other than men. He established the brand of feminism where one doesn’t need to reduce men to get equal representation for females.

Going back to Pather Panchali’s third act: All three of them pack their bags. They’re leaving for Benaras. There is no empathy left for this place in Harihar’s heart anymore. “Thanks for everything you did for us” Sarbojaya tells her sister-in-law. “Perhaps not enough,” she answers, “for you’d have stayed if we’d have helped you adequately.”

In the ending shot, they are sitting on a bullock cart at the beginning of their journey to Benaras. This pretty much sums up their life: a neverending journey, farce and repetitive to an extent that it seems absurd. After all Pather Panchali literally means ‘narration of the path’.

Camus saw how uninteresting Sisyphus’s life was. He was curious about what Sisyphus might think when he pushes that boulder up the hill, about his farce, repetitive and absurd life, and about why his life is worth living even after so much pain and failure.

If we see Pather Panchali as a standalone film and separate it from the rest of the trilogy, we would also ask the same questions: How to make sense of their life? Was all the pain worth it? How must they survive in a city as big as Benaras or would agony follow them? Camus also wanted to make sense of Sisyphus’s life. He had an interesting conclusion about Sisyphus living his failure-ridden life and about what he thinks while pushing that boulder. He said “We must imagine Sisyphus happy.”