‘Good Will Hunting’ is Good to Watch for Mental Health Month

The relationship between Will and Sean is the best part of the movie. It’s always a delight to see Robin Williams on screen

Incluvie Foundation Gala - Learn More

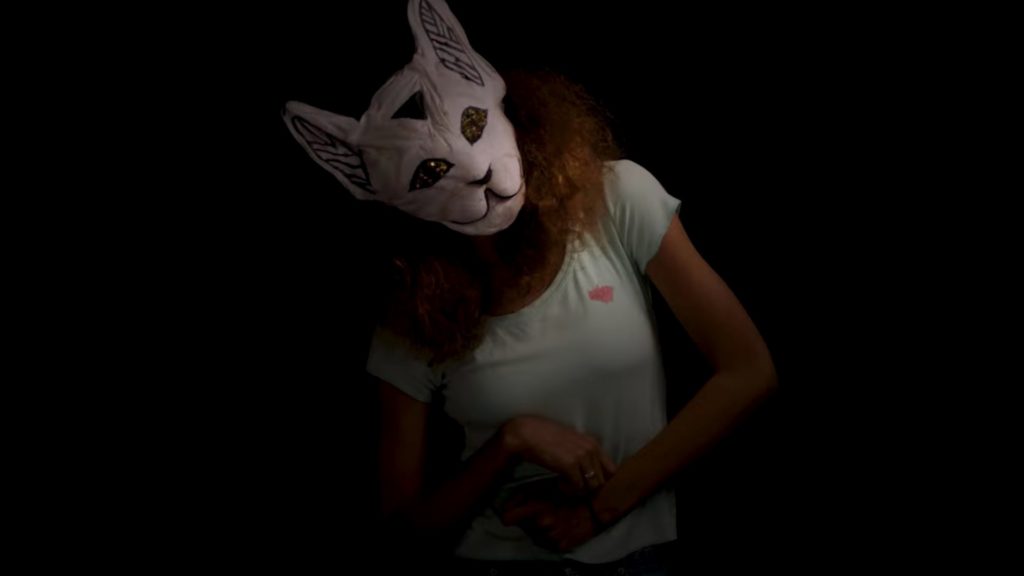

Madeline’s Madeline, a 2018 film directed by Josephine Decker and starring Helena Howard in the titular role, follows a young girl who is part of a professional acting troupe. As Madeline’s dedication to her work grows, and as her relationship with her mother (Miranda July) grows more and more fractured, the lines between Madeline’s real life and her stage life begin to blur. What follows is an emotional, frightening, and dreamlike story looking at the way in which actresses are exploited because of their vulnerabilities, and how often this exploitation is overlooked.

Madeline’s Madeline isn’t an easy watch, for various reasons. It’s not a movie that will appeal to everyone (though I personally found it brilliant), and it’s one that the audience needs to digest before forming a real opinion. It’s a tough movie, and all of its aspects, from the camerawork to the writing to the performances, are heavily anxiety-inducing. The film has merit as a thriller, and there are plenty of frightening moments throughout that make the audience question how dark the film will actually become.

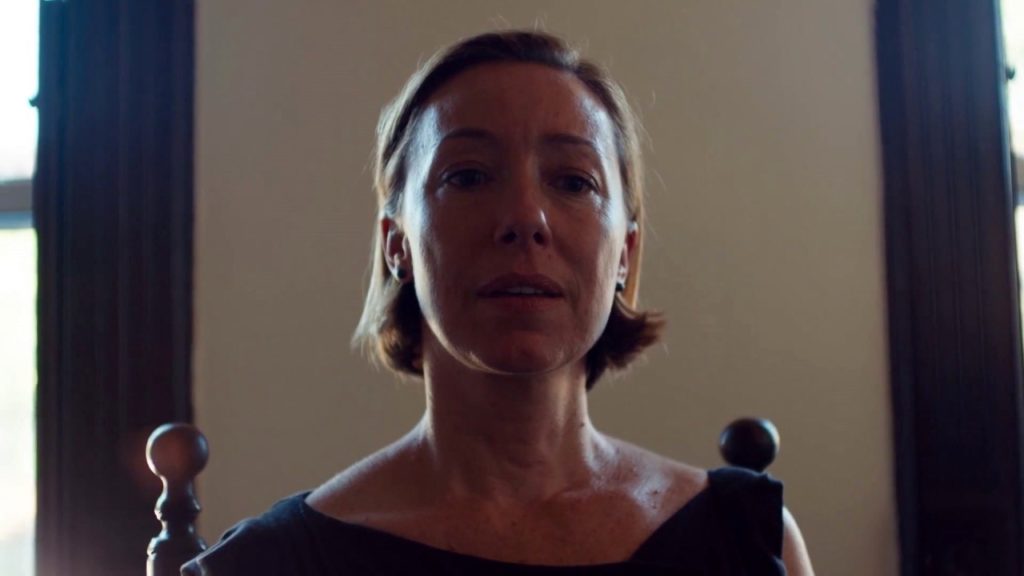

What’s most difficult to watch is the way in which Madeline’s vulnerabilities are taken advantage of by Evangeline (Molly Parker), the director of Madeline’s acting troupe who Madeline looks up to as a mother figure, oblivious as to how Evangeline is taking Madeline’s pain and using it to heighten her own work.

Evangeline regularly takes advantage of things Madeline tells her in private; at the beginning of the film, a dream is shown in which Madeline fantasizes about hitting her mother’s hand with a hot iron. Evangeline takes this and makes it into an acting exercise, not caring enough to notice how she is exploiting Madeline’s fears and anxieties. It is made known that Madeline, prior to the beginning of the movie, was in a psychiatric hospital for an undisclosed mental illness; though she is now on medication, her major struggle is still her mental health, and Madeline doesn’t see the signs that Evangeline is using her pain for her own purposes.

The film starts off subtle in its depiction of the mistreatment of actresses, letting Evangeline gain the audience’s trust — at the start, she, by all means, appears as a safe haven for Madeline, someone who helps her escape her difficult home life and transform her pain into art. Decker manipulates the audience in this way, similar to how Evangeline manipulates Madeline into idolizing her.

As the story continues, however, it becomes more and more difficult to watch as Evangeline’s true intentions become clear. As many directors do, Evangeline pushes Madeline to her limits, taking the girl’s vulnerabilities and using them against her to make art that is, in her mind, perfect.

In a world where directors abusing and exploiting their actresses is normalized for the sake of great art—take Alfred Hitchcock with Tippi Hedren and Stanley Kubrick with Shelley Duvall, for example, along with many others—Madeline’s Madeline sparks an important discussion about what boundaries should be set between stage life and personal life. Specifically, Decker looks at how these boundaries are pushed and violated in the case of actresses, who too often are taken advantage of for their vulnerabilities and mistreated as a result.

Few people take the pattern of actresses being abused and exploited as seriously as they should — there is the idea in Hollywood that, if exploitation results in a brilliant performance, that exploitation is acceptable, regardless of the psychological damage it may cause for the actress. It is important to note that, such as with the directors previously mentioned, the exploitation of stars is almost always centered on women, who are too often mistreated at the hands of (typically male) directors.

Women are exploited in nearly every way in the name of great art, whether this is mentally, physically, sexually, etc. In an industry where actresses are typically discarded or typecast after they hit a certain age, it’s no surprise that so many of them tell stories about how they were harmed or mistreated on set. Though other films have looked at the way in which Hollywood discards women as quickly as they take them, such as David Lynch’s Mulholland Drive, none have done so in the way Madeline’s Madeline has.

Madeline’s Madeline, therefore, begs the question—is there a point where pushing actresses to give their best material becomes too far, and why is this practice so normalized in Hollywood? Many people point to a pattern of mistreating actresses leading to great performances and excuse the act because of this. In protest of that idea, Madeline’s Madeline shows the harm that can result from this mistreatment, and, by all means, condemns directors for exploiting actresses for their own vision. It asks the audience how far is too far in these situations, and why a great performance is prioritized over the health and wellbeing of the actress.

The film’s ending is powerful, depicting Madeline and her entire acting troupe—after a personal acting exercise that pushes Madeline too far—rebelling against Evangeline and making their own show, which is strange and mesmerizing all at once. Within the ending, the audience can understand that great performances don’t have to come from a place of exploited vulnerability and that the abuse of actresses isn’t a necessity in creating these performances. They can act just fine on their own, and Hollywood excuses directors far too often for their damaging practices.

Madeline’s Madeline does not fall short in terms of diversity, either. The film, led by a Black woman, is driven by its female characters. The men in the film are either absent or inconsequential; women own this story, and their choices solely determine where the plot of the movie goes. Given that the film is directed by a woman, its call for the end to the exploitation of actresses feels even more powerful and relevant. Decker focuses specifically on the way women are treated within the entertainment industry and the inherent misogyny that exists within Hollywood.

Though Hollywood, much like Evangeline, does its best to hide behind a façade of progressiveness, it ultimately exploits women and uses actresses until they are deemed undesirable. The film’s honest portrayal of abuse and manipulation that is inextricably weaved into the industry is refreshing, and, though the film can often feel brutal, it is undeniably important.

(This article was originally published by Marisa Jones on Medium.)

Related lists created by the same author

The relationship between Will and Sean is the best part of the movie. It’s always a delight to see Robin Williams on screen

Related movie/TV/List/Topic

We're making today a perfect day for you, and for everyone.