The Kardashian's 'Pick Me' Brand of Empowerment on New Hulu Show

On their new show, The Kardashians, the famous family continues to use their personal lives as advertisements for thier billion-dollar businesses.

Incluvie Foundation Gala - Learn More

Ah, Dead Poets Society. The infamous 1989 film that takes place in 1959, which unintentionally became self-referential in 2013 when Robin Williams died by suicide. Looks like there’s a dead poets society in real life too.

Robin Williams has a gift for playing father figure characters. However, this is very different from playing a father. Father figures tend to denote taboo: an emotional intimacy between two men who aren’t related. Generally, male mentor relationships don’t transcend what is being mentored. For example, coaches teach struggling kids to find solace in baseball. Implicit wisdom is imparted. Explicitly stating this wisdom would mean opening up about a tale of hardship, which men don’t often do. Instead, they impart stoic emotional fortitude onto the next generation by teaching young people to emotionally invest in activities that don’t require reflection. But Robin Williams’ characters take a different approach.

The taboo of Robin Williams’ father-figure characters makes them compelling. If a mother figure instilled wisdom in a young girl, no one would take pause because the patriarchy expects women to maintain a caring facade. Men label much-needed commiseration about patriarchal oppression as “girl talk” in order to trivialize it and deny their own role in propagating the patriarchy. That’s why, when men confide in each other, people take a pause. What could they have to talk about?

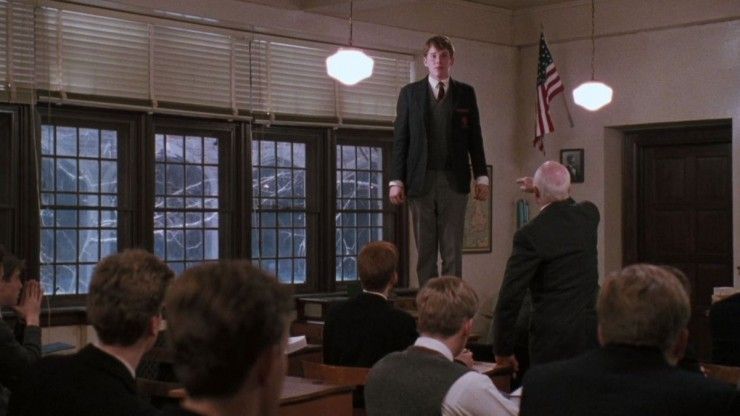

In Dead Poets Society, Williams plays the repressed John Keating, an English teacher at the fictional Welton Academy in Vermont. When Mr. Keating advises his student, Neal (Robert Sean Leonard), to audition for the school play, it evokes taboo not only because doing so would defy the boy’s father, but because Keating is defying the emotional suppression pact most men sign. When Neal participated in the school play, he gave the middle finger to a system that privileges him greatly and oppresses him only marginally. Because of his complacency in this system, Neal (and Mr. Keating) only seek to dismantle it insofar as to liberate himself.

In Good Will Hunting, (1998) Robin Williams reprises his father figure role in a film with a happier ending. The therapist of troubled Will Hunting (Matt Damon), Williams’ character, Sean Maguire, elicits tears from Hunting by the end of the film. Hunting grew up in the care of abusive foster parents and was sent to Maguire after a college professor discovered the boy’s secret mathematical genius. In this role, Williams mentors Hunting and act as a confidant, similar to his role in Dead Poets Society. Because Will Hunting faced internal obstacles, once Maguire helped him bypass them, he could find happiness. However, because Neal faced external obstacles (his father’s opposition), once Mr. Keating emotionally awakened him, he faced these immovable obstacles with even more misery. Mr. Keating revealed an emotional world to Neal that became tortuous due to the stubbornness of his father.

Neal’s father, played by Kurtwood Smith from That 70’s Show, insists his son will one day become a Harvard-educated doctor. He exists as an authoritarian father figure in the vein of many young adult movies. These types of parental figures impose suffocating rules on their children, supposedly for the children’s benefit. Yet, they can’t comprehend the emotional reality those rules create for the children.However, Dead Poets Society takes a unique angle on the archetypal YA-movie dad by giving the audience a glimpse into Mr. Perry’s perspective.

Mr. Perry confesses, “Your mother and I just don’t understand why you keep defying us.” Children often assume that when parents impose rules, those rules come in spite of an understanding of the child’s opposition to them. However, Dead Poets Society reveals parents are just as clueless about their children as children are about their parents. Mr. Perry’s genuine exasperation reveals he has no idea why the rules he has imposed prove torturous for his son. He truly believes he knows best. He only understands the parameters of his plan for his son. He does not understand his son.

At the end of their confrontation, Neal almost offers an explanation as to why he cares so much about acting. But, seeing his parent’s exasperation, he realizes that even in their rigidity they have no bad intentions. What’s the point of trying to get them to understand his perspective? He’s not fighting the battle he thought he was. Was his father even the enemy anymore? Or is the enemy the intangible hand of fate that placed him in this situation? If the latter is true, there is only one way to win the battle.

Neal’s death by suicide signified a climactic coming of age moment. He had accepted the reality of his parent’s adult personalities. He no longer saw them as the deities of early childhood or the thoughtless oppressors of teen years. Instead, his suicide indicated he saw their real personalities and could not accept them. The adult identities of parents cannot be changed by teenage rebellion. In seeing their irredeemable, unchangeable selves, Neal realized he couldn’t face the people his parents were – or the person they expected him to be. He couldn’t live his life pretending.

After Neal’s suicide, the school conducts an inquiry into Mr. Keating’s lessons. This involves forcing several students to sign a paper confirming the school’s version of events, which holds Mr. Keating responsible for Neal’s suicide. At the end of the film, the Headmaster, Mr. Nolan (Norman Lloyd), summons Todd (Ethan Hawke), Neal’s former roommate, to his office to sign this form. His parents urge him to sign it. The scene ends with a shot of the Headmaster holding out a pen in Todd’s direction. The audience never finds out if he signs it. In the film’s final scene, however, Todd blurts an apology to Mr. Keating. He says, “They made everyone sign a-” before a faculty member cuts him off.

In the final scene, Neal’s former classmates stand and salute Mr. Keating as he packs up his belongings, a tribute inspired by Todd, who stood up first. This scene mirrors many young adults shows where a rogue peer inspires his compatriots to rebel against the nasty adults. In Season 1, Episode 5 of Netflix’s Sex Education, in a high school auditorium during an assembly, every girl stands up proclaiming, “It’s my vagina!” in order to cover for a girl whose nudes were leaked. Although in Dead Poets Society, we never find out if Todd was rogue enough to refuse to sign the form, we know he had the courage to face Mr. Keating. The lewd proclamation on Sex Education may seem trivial in comparison, but it speaks to the universal desire among young adults to find unity against authority.

En masse rebellions allow viewers to relish the thrill of defying authority. However, the mystery of whether or not Todd signed the form placates the viewer. Audiences want to believe that Todd refused to sign the form because they want to believe that, if put in Todd’s place, they wouldn’t sign the form either. But isolated from peers, surrounded by authority figures, who wouldn’t crumble? To cater to those who believe Todd stayed strong, director Peter Weir let this part remain a mystery.

Dead Poets Society tells a young adult story with adult complexity and nuance. However, unlike many adults who tell young adult stories, writer Tom Schulman and director Peter Weir don’t bestow their characters with that nuance. Many stories that channel young adult narrators do this, however. For example, Taylor Swift wrote her 2020 song “betty” from the perspective of a seventeen-year-old. (Swift is 31). The chorus: “I’m only seventeen, I don’t know anything.” It’s clear an adult wrote this song. What seventeen-year-old would admit they don’t know anything?

Conversely, the seventeen-year-olds of Dead Poets Society are so deep in the trials and tribulations of young adulthood they don’t have time to pause and reflect on how little they know. Similarly, at eighteen, Taylor Swift wrote the ballad “Fifteen.” “When you’re fifteen and/somebody tells you they love you/ you’re gonna believe them,” she sang. Although she was three years removed from the time period she wrote about, as a teenager, she still wrote about young adulthood in real-time.

In this sense, Dead Poet’s Society is equivalent to Taylor Swift’s “Fifteen” as opposed to “betty.” The film doesn’t pause to reflect with generous hindsight as Swift does on “betty.” Instead, it addresses the concerns of its teenage protagonists in real-time, avoiding an adult perspective that would diminish the film’s high stakes. Weir presents Neal’s anguish over his disagreement with his parents as paramount as it would feel to a teenager.

For all its young adult heart, and thematic similarity to Disney’s Lemonade Mouth, Dead Poets Society is certainly an adult movie. Although told with compassion for its teen-aged protagonists, the heavy subject matter lands unadorned. Adults will recognize the plight of repressed English teacher Mr. Keating, who, despite his personal failings, hopes to pass on his wisdom to the next generation. Instead, that lineage stops short with Neal’s untimely death, and Mr. Keating loses his job. Although a mentor to students, Mr. Keating experiences the key experiences of young adulthood in the film: emotional repression, clashes with authority, and punishment for events set in motion with good intentions. Although a teacher, Mr. Keating learns the essential life lesson that often nothing changes from childhood to adulthood.

Robin Williams’ untimely death in 2013 speaks thematically to his work in Dead Poet’s Society. Often, the most profound, heaviest emotions make this life the most unbearable. In theory, the emotions that Mr. Keating unlocked in Neal, such as a passion for theatre, self-confidence, and a desire to rebel, are positive. But because Neal’s circumstances prevented him from expressing them, feeling them became torture he couldn’t bear. Maybe the Dead Poets Society doesn’t just refer to bygone writers like Henry David Thoreau. It could refer to any emotionally repressed writer who feels unable to express themselves- who feels dead inside.

For all its philosophical wisdom, Dead Poet’s Society is a focused on LGBT, queer, white, heteronormative fantasy that ignores the fact that, in real life, its central storyline would most likely be queer: at an all-boys school, a teenager rebels against his father and joins the drama club. Sound familiar? However, if the story had been queer, and concluded with Neal’s suicide, it would have fit into the unfortunate cannon of queer stories that fail to reward their characters with the endings they deserve. Another one of those stories would make me want to be a dead poet.

Related lists created by the same author

On their new show, The Kardashians, the famous family continues to use their personal lives as advertisements for thier billion-dollar businesses.