The Heroes of "Hustlers"

"Hustlers" returns power to groups that are traditionally deprived of it: women, the working class, and sex workers.

Much like Kramer vs Kramer, this ironically named movie follows the disintegration of a marriage and the legal processes therein of divorcing your spouse (a more contextually harmonious title would be “End of Marriage Story” or even “Divorce Story”). But Noah Baumbach names his film Marriage Story because the premise he chases after is something like “love conquers all, even divorce.” This is why he oscillates between the little expressions of love and couples that with the vehement anger and disgust expressed by our two ill-fated lovers, Charlie and Nicole.

These characters share a son, Henry, whose custody and place of living is the main question they argue about. Both Charlie and Nicole feel like they lose their agency and control to their attorneys in the divorce process. The divorce lawyers construct an illusory version of the truth in order to win the case rather than listening to the truth that organically emanates from the characters. This seems like a good metaphor for the film as a whole, where the illusion of “real” takes precedence over the authentic.

Which brings us to our emotional stakes. Marriage Story feels like it sprung from the mind of a theater director who wanted to put up a play where the only note was to “be real”. And so, as often these plays become, it transmogrifies into a clinical study where true emotion gets substituted for sensational artifice.

The image of “real’’ is carefully crafted, as if designed by a lab that dictates where to place the likable scenes and where to inject the exposure to the darker sides of human nature. Have Nicole give him a trumpet here to make us like her at this moment in time. Have the stage director touch Charlie’s thigh here to make sure we know something morally ambiguous is going on. It becomes so tirelessly technical that I didn’t care much for the relationship between Charlie and Nicole. Instead, I saw all the little buildups where the director indicates how the audience should feel rather than organically letting us decide on our own. Examples of these moments are whenever an inauthentic tableau appears for the sole purpose of reminding audiences that film is a visual medium. This is perfectly illustrated whenever Charlie and Nicole both hold onto their son and he is caught in the middle. A pictorial metaphor so cliche and unsubtle that I rolled my eyes every time this happened (read: at least 3 separate moments of the film.)

Another instance is when Charlie comes over to help Nicole close her gate and as they close the gate on each side, they stare at each other symbolically closing the door on their marriage. I don’t think the filmmakers could have made these moments any more obvious to the viewer, it’s as if this movie were shouting to us: “you are stupid! This is what’s happening!” Baumbach doesn’t trust the audience’s intelligence or ability to understand the subtleties of loving someone while hating them, too.

I doubt that the characters of Charlie or Nicole, who consider themselves artists, would enjoy this movie. Let’s pick apart the hackneyed emotional climax. Scream, scream, sob. “Yes, yes, good, keep that emotion,” says the theater director. This comes more from the realm of acting exercise than anything I’ve ever seen in real life, ever. I have, however, seen this scene countless times in plays and staged productions. I felt nothing during this scene. It didn’t offer anything new to say and passed by all the tropes of lovers’ quarrel since Euripides’ Medea. Charlie even punches a wall while shouting “you’re f***ing winning!” as if to reaffirm his masculinity after feeling like it’s being taken away from him by his ex-wife. Every moment is so wrought that it feels like it was written by a bot who was forced to read tragedies and penned this a couple of minutes later.

As someone who’s seen his parents’ marriage fall apart at a young age, I can say that the kid was quite passive and did not have much of a personality. The movie was not focused on the kid and there was never a moment of real danger like in Kramer vs. Kramer when Dustin Hoffman heartbreakingly races through traffic to get to the hospital. The paradox in the Kramer vs. Kramer scene is that by being a good father and rushing to get medical attention after his kid falls, the court will only see him as a negligent father who lets his kid fall on the playground in the first place. And then, he has to battle the doctors to stay in the room to take care of his son who’s painfully getting stitches. Those are real emotional stakes. He is fighting for his son and asserting his role as a father who’s here to take care of him. And I think the reason that Marriage Story lacks a situation like this is that the kid, Henry, never drives the story. The movie thus lives up to the “Marriage” aspect of the title while leaving out the fruit of their marriage, their parenthood, on the backburner.

The closest comparison is the scene where the interviewer comes over for dinner and Charlie accidentally cuts himself with a blade he thought was retracted. But the interviewer is so subdued and kooky that we don’t feel any danger. Charlie even falls to the ground after the cut, making the viewer think he’s gonna pass out while his kid innocuously walks over him. And then…. Charlie is absolutely fine in the next scene. The stakes seem only to be emotional and the kid is simply not involved. Charlie doesn’t fight for his kid in the same way Ted Kramer does. The real fight in Marriage Story, so it seems, is LA vs. NYC. This takes away the immediate stakes of the crumbling family and propulses into the clinical debate which relies on superficialities. New York produces geniuses with MacArthur Grants, LA has money and space. These are extremely reductive views of two culturally rich cities. This does a disservice to the movie as the heart of the disagreement is an everyday debate in the artistic circles of both central characters. This serves more to fuel the LA vs. NYC mentality of filmmakers and takes away from the most psychologically rich part that could’ve been explored a lot more: the kid, Henry.

This seems contradictory because what the parents are fighting about appears to be about custody but if you dig deeper, it is actually not. This is why, while this film is technically proficient, it lacks the emotional maturity to guide the audience rather than indicate to the audience how to feel.

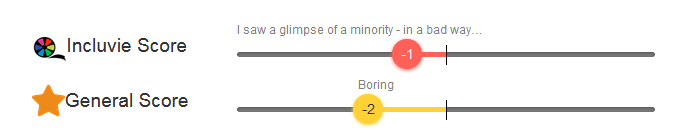

Finally, a note on diversity. Marriage Story lacks diversity. The story revolves around two affluent white New Yorkers who can afford a bicoastal LA-NY divorce while working in the arts. Charlie can fly back and forth pretty frequently to see his son, who lives with his mother Nicole. Both parents pay for quite expensive lawyers, and in the end, they don’t really lose anything. Also, the only people of color are a couple fighting at the courthouse for half a second. Yikes.

(This article was originally published by Mick Cohen-Carroll on Medium.)

Related lists created by the same author

"Hustlers" returns power to groups that are traditionally deprived of it: women, the working class, and sex workers.