A gay ice skating anime made me believe in love again

'Yuri!!! on Ice' turned queerbaiting on its head and gave me hope when I needed it the most.

Incluvie Foundation Gala - Learn More

From Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein to Octavia Butler’s groundbreaking works of Afrofuturism, women have always been pioneers when it comes to science fiction. Of course, you probably wouldn’t know that from looking at cinema’s biggest sci-fi hits. But despite Hollywood’s ongoing bias toward stories by and about men, women are integral to many science fiction films, ranging from classic blockbusters like Star Wars to critically-acclaimed dramas like Children of Men. This Women’s History Month, I wanted to celebrate these iconic characters (and the women who play them) for bringing so much to my favorite genre. In no particular order, here are 10 amazing women in science fiction films.

Guillermo del Toro’s robot-versus-monster slugfest delivers everything I want from a kaiju film: stunning visual effects, epic fights, and just the right amount of camp. Pacific Rim also boasts a diverse international cast and breaks from the strain of American exceptionalism that often runs through apocalyptic stories. While one of the film’s protagonists is a white man, Raleigh (Charlie Hunnam) shares a mech and the spotlight with Mako Mori, played by Japanese actor Rinko Kikuchi. Mako’s character arc follows the underdog-to-hero trajectory that’s often reserved for men. Despite her relative inexperience, she proves that she can hold her own against Raleigh and deserves to fight kaiju alongside him. Mako gets some truly badass moments during combat (two words: chain sword), but she also brings a surprising amount of emotional gravitas to what might otherwise be a one-note action film. From her tragic backstory to her accurate portrayal of PTSD to her touching relationship with her adoptive father Stacker (Idris Elba), Kikuchi’s performance ensures that the audience never forgets the human cost of disaster.

Pacific Rim is available on Hulu.

Science fiction doesn’t have to be about action, alien contact doesn’t have to involve combat, and women don’t have to kick ass to be badass. Arrival takes a cerebral approach to a first-contact narrative, delving into questions of geopolitics, linguistics, and the very nature of cognition. Amy Adams stars as Dr. Louisa Banks, a renowned and lonely linguist who takes on the daunting task of communicating with aliens who arrive on Earth for unknown reasons. Louisa stands her ground amid a group of men predisposed to see the aliens as a threat. She calmly but firmly advocates for the value of communication over preemptive aggression, which is a refreshing contrast to the militaristic and colonialist tenor of many first-contact films. In addition to representing women in science, Louisa represents a field of so-called soft science. The social sciences are underappreciated in real life and underexplored in science fiction. Arrival also stands out for its non-linear storytelling and psychological complexity. The film delves deep into Louisa’s psyche, exploring the growing anxiety and turmoil that lies beneath her collected exterior. Adams was the perfect choice for this role, especially because the weight of Arrival’s brilliantly executed plot twist rests on her shoulders. Her subtle and heartwrenching performance makes sense both before and after the mindblowing reveal—no easy feat.

Arrival is available on Amazon Prime.

Children of Men made for an eerie rewatch this year. The film takes place several years into a medical crisis that spurred a wave of social upheaval, racism, and anti-immigrant rhetoric. Rather than a contagion, humanity faces seemingly universal infertility. People turn to violence as they grapple with our species’ impending extinction. Alfonso Cuarón based the film on a novel by PD James, and Children of Men is one of the rare film adaptations that I prefer to the source material. One of the most significant additions to James’s original story is Kee (Clare-Hope Ashitey), an asylum seeker and possibly the only pregnant person on Earth. The protagonist, Theo (Clive Owen), is tasked with protecting Kee and escorting her to a scientific group that hopes to cure infertility. Kee represents hope for both Theo and humankind as a whole. As such, she could have easily become a Madonna-like symbol or a living plot device. Fortunately, Ashitey fleshes her out into a fully realized character in her own right. Kee jokes unabashedly about her sex life, refuses to be exploited for political purposes, and isn’t afraid to assert herself with both her captors and her protectors. She’s also an undocumented immigrant seeking safety for herself and her child, and it’s therefore very meaningful for the film to emphasize the importance of supporting Kee and other women like her.

Children of Men is available on Peacock.

When Alien premiered in 1979, it awed the world with its grotesque practical effects and flawless synthesis of science fiction with slasher horror. However, casting a woman as an action protagonist may be the film’s most groundbreaking and enduring choice. Famously, Ellen Ripley wasn’t originally written as a woman. I have some reservations about this approach to female characters—what does it say about a man if he can only write well-rounded women by not thinking of them as women?—but in Ripley’s case, it’s hard to argue with the results. Sigourney Weaver brilliantly balances Ripley’s competence and level-headedness with the level of fear and vulnerability that the story requires. Simply putting a woman a the helm of an action film was game-changing at the time, but just as significantly, her motivations have nothing to do with men and her abilities are far more important than her appearance. In addition to her physical prowess, Ripley demonstrates intelligence and creativity during her showdown with the xenomorph. Also, let’s be honest: the events of Alien could have been avoided if the crew had just listened to her in the first place.

Alien is available on Hulu, HBO Max, and Amazon Prime.

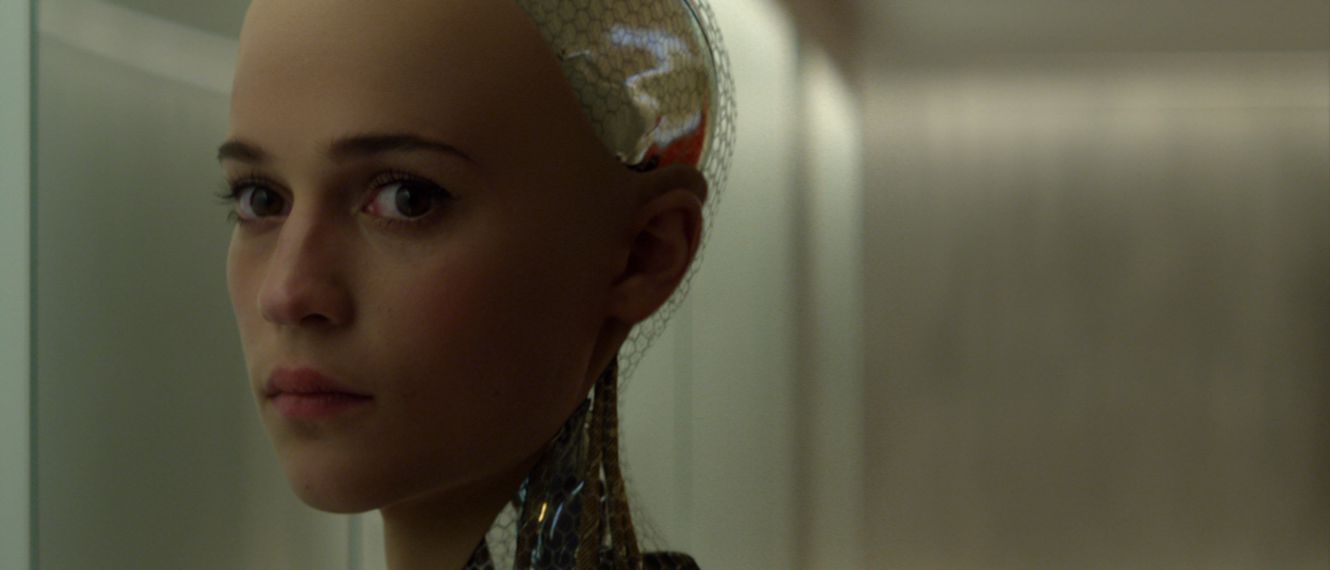

Some of science fiction’s most fascinating explorations of gender come in the form of robots and androids. As human-made (and often literally manmade) constructs, robots that resemble women can reveal their creators’ ingrained ideas about gender—which, of course, parallels storytelling itself. Just as writers often write their misogyny into women, inventor Nathan (Oscar Isaac) programs his misogyny into the robots of Ex Machina. One of these robots is Ava (Alicia Vikander), who Nathan claims to possess artificial intelligence. As a sentient being held captive by a narcissistic creator, she elicits attachment and protectiveness from Caleb (Domhnall Gleeson), a young man visiting Nathan’s remote mansion. Vikander’s performance walks the challenging line of holding our sympathy while maintaining an air of uncertainty about her true nature. Ava teeters on the edge of the uncanny valley. Her human face and seemingly genuine expressions of emotion juxtapose eerily with her transparent torso and Vikander’s subtly off physical movements. She keeps both Caleb and the audience on tenterhooks, simultaneously entranced and disturbed by her, unsure if she’s a threat or a victim. The result is both a tense thriller and an astute commentary on the powers and pitfalls of human imagination. Ex Machina tells an engaging story while also commenting on the stories men tell about women, the stories humans tell about machines, and the stories we tell about ourselves. As the film brilliantly demonstrates, the risks of believing our own constructed realities can be deadly.

Ex Machina is available on Hulu and Showtime.

Yes, I know. Jupiter Ascending is, to put it generously, a hot mess of a movie. It’s also a feminist reconstruction of the “chosen-one” sci-fi blockbuster. The genre is saturated with movies that function as wish-fulfillment for (usually straight, white, and cis) men. Men regularly get the chance to see themselves as the hero of a story where they journey through space, save the galaxy, and get the girl. As many critics have pointed out, Jupiter Ascending offers a similar escapist fantasy for women. Jupiter (Mila Kunis) is a relatable everywoman working as a janitor whose life turns upsidedown when bees identify her as space royalty. Really. She’s swept into a galactic power struggle that threatens to wipe out humanity. Jupiter retains her endearing awkwardness throughout her journey and reacts the way women in the audience might to the chaos unfolding around her (namely, with a mix of excitement and utter confusion.) Despite the film’s many flaws, it’s got a lot going for it: gorgeous CGI, Eddie Redmayne hamming it up in a cape, Channing Tatum as a hot werewolf-angel-alien-boyfriend, space roller skates, and So. Many. Bees. Does it make any sense? No. Is it well-written? No. It’s a stupid, fun, trashy power fantasy. And you know what? Women deserve stupid, fun, trashy power fantasies, too.

Jupiter Ascending is availble on Netflix.

Nichelle Nichols broke barriers when she appeared in the original Star Trek series as the Enterprise’s communications officer and one of the few Black women on TV. Uhura inspired the likes of Whoopi Goldberg and astronaut Mae Jemison. However, after the series’s first season, Nichols grew frustrated with her limited role on the show and considered returning to Broadway. None other than Martin Luther King Jr. convinced her to stay—and thank goodness he did, because I can’t imagine the show and the ensuing films without her. Uhura gets some shining moments in the first six Star Trek films. She plays an instrumental role in The Search for Spock, taking an undercover position at a remote station that allows her to help her crewmates at a crucial moment. Nichols later gets to show her comedic chops in The Voyage Home (a.k.a. the one with the whales, a.k.a. the best Star Trek movie.) I’m also a huge fan of her adorable late-blooming romance with Scotty. Zoe Saldana carries on Uhura’s legacy in the reboot films and gets some incredible moments of her own, from staring down Klingons in Into Darkness to uncovering the antagonist’s true identity in Beyond with her knowledge of linguistics.

All Star Trek films are available on Paramount+ and some are available on Hulu.

Castle in the Sky is Studio Ghibli’s first film, and it codifies many of the elements that went on to make director Hayao Miyazki’s work so universally beloved: luscious animation, a fascination with flight, antagonists who eventually reform and side with the heroes, environmentalist and anti-war messages, steampunk aesthetics, and—most relevantly to this article—a female protagonist. Sheeta is an early entry into a long line of powerful Miyazki heroines. At the beginning of the film, she’s been abducted by the villainous Muska who wants to use the powers he and Sheeta inherited to dominate the planet. She escapes and quite literally falls into the arms of a boy named Pazu. While Pazu initially seems positioned as her savior, it is ultimately Sheeta who saves not only Pazu but an entire civilization. Part of what makes Sheeta such a compelling protagonist is her vulnerability. She’s a child forced into challenges that she never anticipated or asked for, but she pushes through her fear in order to stand up against tyranny and defend the people she cares about.

Castle in the Sky is available on HBO Max.

Bubs is the second robot on my list, but she couldn’t be more different from Ava. Space Sweepers is an entertaining, political, and surprisingly touching take on the space western subgenre, and Bubs matches the film’s tone. Her sharp wit and telling-it-like-it-is attitude deliver much of the film’s comedy, but her character arc is also a heartwarming exploration of transgender womanhood. Bubs was built to be a weapon, devoid of individuality and femininity, but she’s grown beyond her programming and developed an identity of her own. While her crewmates initially misgender Bubs, we soon learn that she’s saving up for the robotic equivalent of gender affirmation surgery. This aspect of her character is treated with sensitivity and dignity. One of the film’s sweetest scenes takes place between Bubs and a young stowaway who, unprompted, refers to Bubs as a lady. Bubs’s overwhelmed and delighted reaction at having her gender recognized moved me, instantly making her both my favorite character in the film and one of my favorite fictional robots of all time.

Space Sweepers is available on Netflix.

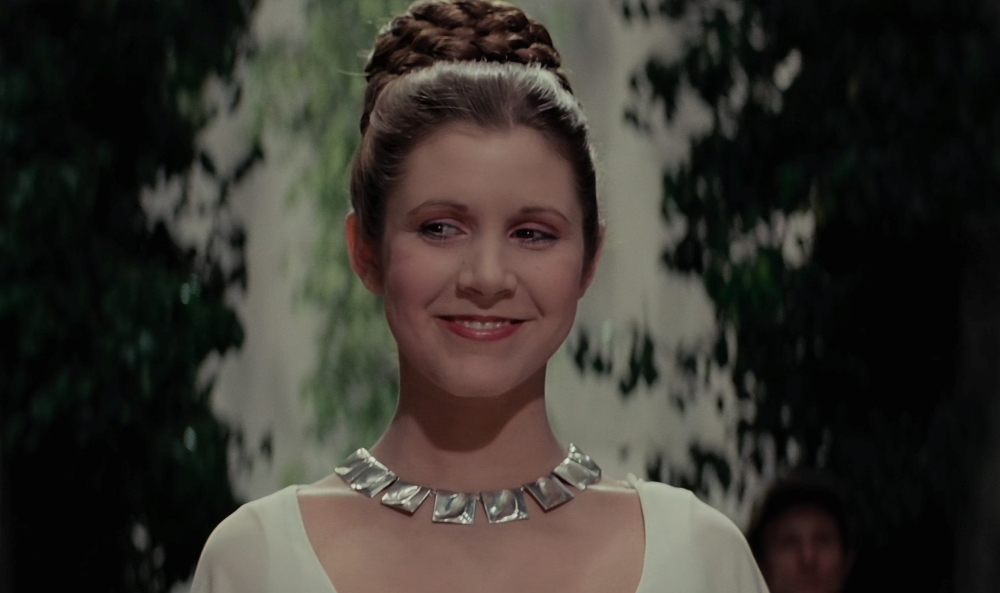

No list of women in sci-fi would be complete without her. A princess, a general, and (as far as I’m concerned) the real hero of the original trilogy, Leia Organa captured fans’ hearts and minds when she stood up to Vader in the very first scene of Star Wars. Leia is unlike many fictional women of her era. Determined, competent, and headstrong, she refuses to let Luke and Han see her as anything but an equal. In the first film, she subverts the “damsel in distress” trope by helping Luke and Han escape the Death Star after they release her from her cell. She goes on to demonstrate incredible leadership skills within the resistance, proving that she can handle herself in political as well as physical conflict. There are aspects of her character that, in my opinion, did her a disservice. I wish that her arc in the sequel trilogy wasn’t so focused on the men in her life, and I’d erase that metal bikini from cultural memory if I could. Nevertheless, Leia remains one of the most iconic and empowering fictional women of all time. Carrie Fisher brought her to vibrant life, imbuing her with Fisher’s own witty charm and pairing her confidence with compassion. Beyond her role as Leia, Fisher is also one of my personal heroes for her openness about her struggles with addiction and bipolar disorder. During her too-short lifetime, Fisher advocated for the acceptance and support of people living with mental illness, making her a hero both onscreen and off.

All Star Wars films are available on Disney+.

Related lists created by the same author

'Yuri!!! on Ice' turned queerbaiting on its head and gave me hope when I needed it the most.